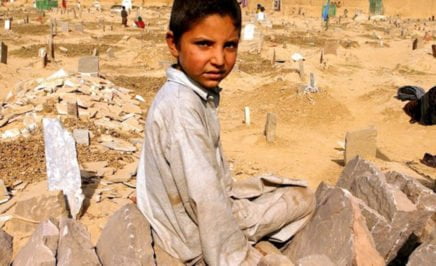

The moment you step outside the airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, the first thing that strikes you are the roses. They are everywhere – lining the dusty motorway into town, clustering flowerbeds in traffic circles, blooming in private gardens.

The second thing you see is fear. Foreigners hide behind their sandbagged walls, barbed wire, armed guards and bulletproof vehicles. But many locals are terrified too, including those who fled the country but were recently returned against their will.

There is every reason to be afraid. The fragile government is struggling to make headway against the Taliban, which is likely more powerful now than at any time since 2001. Other armed opposition groups — including the so-called Islamic State — have seized control of parts of the country and carry out devastating attacks even in securitised areas of Kabul and elsewhere.

Violent incidents are increasingly frequent. According to the U.N., 2016 was the deadliest year for civilian casualties since its records began in 2009. While my Amnesty International colleagues and I were in Kabul in May, a German aid worker and an Afghan guard were killed, and a Finnish woman likely kidnapped, during an attack on a Swedish NGO in the city. The recent horrific bomb attack near the German embassy in central Kabul shows that rather than winding down, the conflict in Afghanistan is escalating dangerously.

British and American authorities warn their citizens against traveling to Afghanistan, saying it remains unsafe “due to the ongoing risk of kidnapping, hostage-taking, military combat operations, landmines, banditry, armed rivalry between political and tribal groups and insurgent attacks.”

“While my colleagues and I were in Kabul in May, a German aid worker and an Afghan guard were killed, and a Finnish woman likely kidnapped”

And yet, Western governments have deemed the country safe enough for Afghan asylum seekers to return. Over the past decade and a half, a number of European countries (as well as Australia) have signed Memoranda of Understanding with Afghanistan, through which the country agrees to readmit its citizens under certain conditions. These types of arrangements are not necessarily unreasonable, but their implementation must conform with international law, which prohibits states from transferring people if there is a risk of serious human rights violations.

Nonetheless, even as the situation in Afghanistan has unmistakably worsened, Western governments have escalated their efforts to return Afghans fleeing war and persecution.

At an aid conference in October 2016, under pressure from the European Union, the Afghan government signed the EU-Afghanistan “Joint Way Forward,” a document that paves the way for the forcible return of an unlimited number of Afghans from Europe. One unnamed Afghan government official called the agreement a “poisoned cup” the country was forced to accept in return for development aid.

Hundreds of returns have taken place since the agreement was signed six months ago. My colleagues and I recently spoke with Afghans deported from Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. While everyone in Afghanistan is at risk, many of the returnees we spoke to were extremely vulnerable, and their returns likely violated international law.

“While everyone in Afghanistan is at risk, many of the returnees we spoke to were extremely vulnerable”

A young man, whom I’ll call “Azad,” is at serious risk because of his sexual orientation. Afghanistan criminalizes same-sex sexual conduct, and there have been reports of harassment, violence and detention by police. When Azad found out he was going to be deported, he tried to kill himself and was put under suicide watch until he was forcibly returned.

This was his first time in Kabul, he told me. “I have nowhere to go,” he said. “Maybe I will join the other drug addicts in the west of the city, just to get some shelter.”

Despite his young age, Azad has survived a number of tragedies. After fleeing the war in Afghanistan as a child, he grew up in Iran, and later lost his mother when the family tried to make its way to Europe. While clearly frightened throughout our conversation, he broke down when speaking about her death. “All I want to do is visit her grave.”

Another man, “Farid,” is in danger of religious persecution for converting to Christianity. Like Azad, he left Afghanistan as a child, grew up in Iran, then fled to a European country. He is terrified about what will happen to him in Afghanistan. Still in shock after being wrenched from his adopted country and faith community, he said: “I feel like I’ve fallen from the sky. I don’t believe I’m here.”

“I feel like I’ve fallen from the sky. I don’t believe I’m here”

He, too, had never been to Kabul. “I don’t know anything about Afghanistan,” he told me. “Where will I go? I don’t have funds to live alone and I can’t live with relatives because they will see that I don’t pray.”

Their stories are, unfortunately, far from exceptional. Some deportees have already suffered violence after being forcibly returned to Afghanistan. An Afghan who returned from Germany in January was injured in a suicide attack near the Supreme Court just two weeks later, according to a recent report by the Afghan Analysts Network. Several other people — including young children — were injured in attacks by armed groups in Kabul, a member of the Afghanistan Migrants Advice and Support Organization told us.

None of these people should have been sent back. When they walked out of the airport, the country was probably as unknown to many of them as it was to me — and they face far greater risks.

European governments and leaders know Afghanistan is not safe. If they don’t stop deporting people like Azad and Farid, they will have blood on their hands.

Anna Shea is a researcher and adviser on refugee and migrants’ rights at Amnesty International.