At a time when racist attacks and hateful speech are on the rise around the world, Amnesty International strongly welcomes the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights’ decision not to water down the Racial Discrimination Act.

Late last year, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull had announced that the Federal Government had set up a parliamentary inquiry to determine whether the Racial Discrimination Act (RDA) – specifically 18C and 18D of the Act – limit free speech.

“The Committee’s decision not to recommend changes to sections 18C and 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act shows a rare glimpse of bipartisan leadership to uphold human rights in this country,” said Stephanie Cousins, Advocacy and External Affairs Manager at Amnesty International Australia.

“Watering down the Racial Discrimination Act would have emboldened those who seek to offend and humiliate other people right at the time we need to come together and denounce such treatment”

Stephanie Cousins

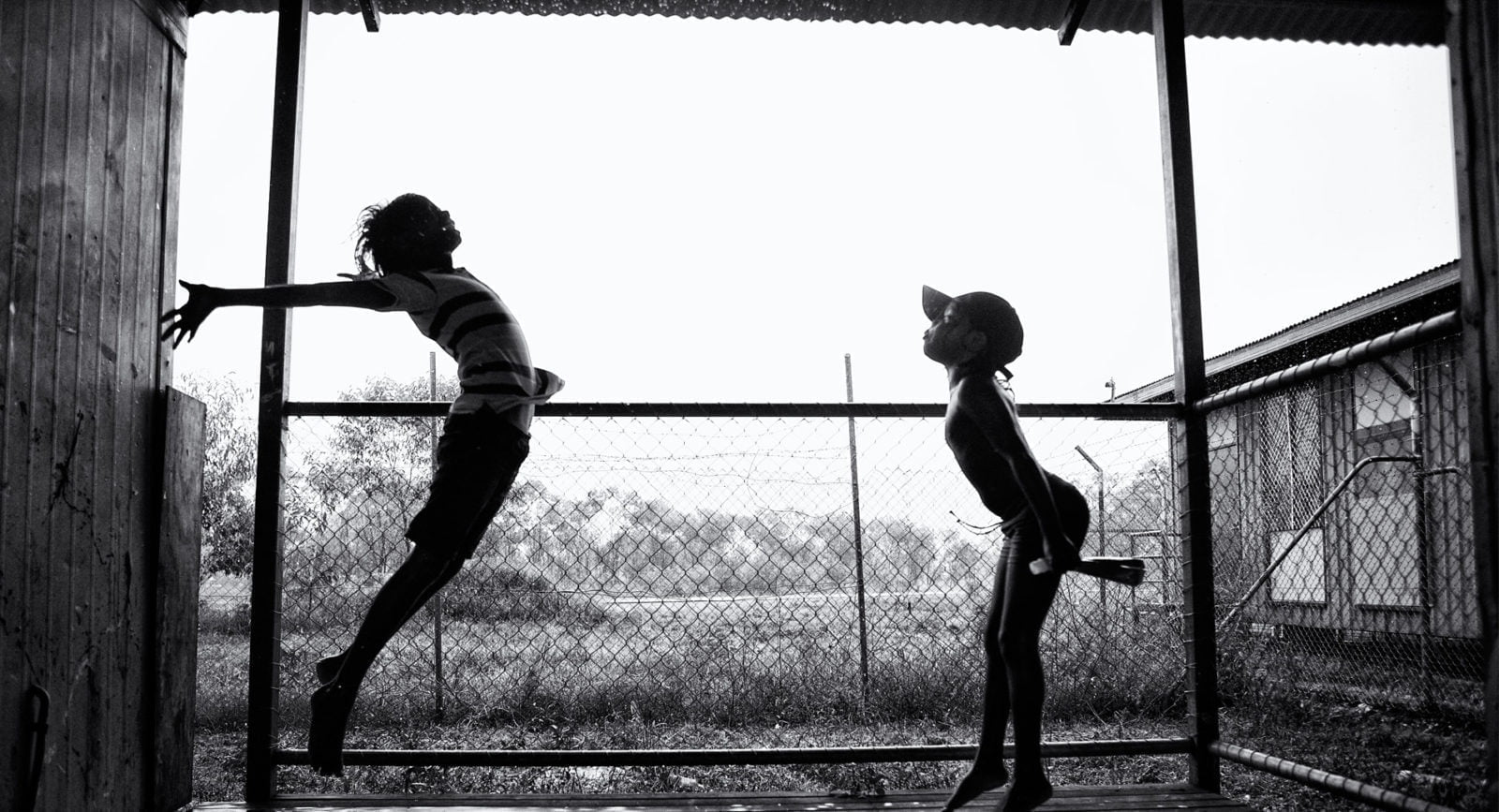

18C and 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act offer recourse to culturally and linguistically diverse people and groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, who continue to suffer racial abuse, vilification and the harmful long term psychological and health effects that result from it.

A rise in racism-related violence

“We’ve seen a rise in racist attacks in the UK and the US, given licence by the hateful rhetoric of their respective governments,” said Stephanie.

“Here in Australia, our government should be doing all it can to protect the one-in-five Australians who endure racism. As the Committee has accepted, watering down the Racial Discrimination Act would have emboldened those who seek to offend and humiliate other people right at the time we need to come together and denounce such treatment.”

Racism has severe impacts on affected communities, contributing to poor mental health, self-harm, suicide, school attendance and workplace productivity.

“Amnesty International welcomes the Committee’s recommendations that all leaders and politicians condemn racially hateful and discriminatory speech when it occurs in public, and that the Australian government invest more in strengthening and developing education programs to address racism in Australian society. These recommendations are needed now more than ever,” said Stephanie.

What is section 18C and section 18D?

The RDA is a law passed in 1975 by the Whitlam government to make sure everyone in Australia was treated equally and given the same opportunities – regardless of their background.

The Act was last updated in 1995 after three major national inquiries – the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody – the National Inquiry into Racist Violenceand the Australian Law Reform Commission Report into Multiculturalism and the Law – found a strong link between racist conduct in public and racially-motivated violence.

At the core of the changes made in 1995 is Section 18C, which makes it unlawful for someone to “offend, insult or humiliate” a person based on the colour of their skin or their cultural background. It also provides recourse for victims of racism to make a complaint to the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC), which then tries to resolve the complaint before it goes to court.

The lesser known Section 18D, brought in at the same time, exempts artistic works, academic and scientific debate and “fair and accurate” reporting of any events or matters of public interest made “reasonably” and in “good faith”.

For more info on the Racial Discrimination Act, read our handy ‘2 minute guide’.

A ‘fine balance’

The importance of protection from racism appears to have been echoed by the Australian Government yesterday, when Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, told the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva that Australia is one of the most “socially cohesive nations on earth” with a “unique model for tolerance, respect, inclusion and integration.

Amnesty believes the Racial Discrimination Act as it stands has managed a fine balance for over 20 years between the right to live free from racism and the right to free speech. The Act provides important protections against harmful racist speech and an avenue for people to make a complaint if they believe they have been subjected to such treatment.

As Amnesty pointed out to the inquiry Committee, 98 percent of the complaints conciliated by the Australian Human Rights Commission result in an outcome that is satisfactory to both parties and very few cases have actually proceeded to court. The Committee has made a number of recommendations regarding the complaints handling procedure at the Human Rights Commission, which we are in the process of reviewing.

“It is paramount that the independence of the Commission is not infringed by any of these amendments,” said Stephanie.

While welcoming the Committee’s decision not to recommend amendments to the Racial Discrimination Act, we believe the Inquiry missed an opportunity to address the genuine threats to freedom of expression and a free press in Australia.

“The Freedom of Speech inquiry should have been an opportunity to look at the laws on Australia’s books that really do restrict freedom of expression – such as our counter-terror laws which criminalise the reporting of special intelligence operations; or our border security laws which criminalise service providers from blowing the whistle when they see abuses against asylum seekers on Manus Island and Nauru. If the government is serious about protecting free speech, let’s talk about reforming these laws,” said Stephanie.

“That the committee did not recommend any changes to the Racial Discrimination Act shows there is no compelling argument to amend section 18C. We urge the Prime Minister to put this question to rest once and for all.”