Human rights abuses against kids

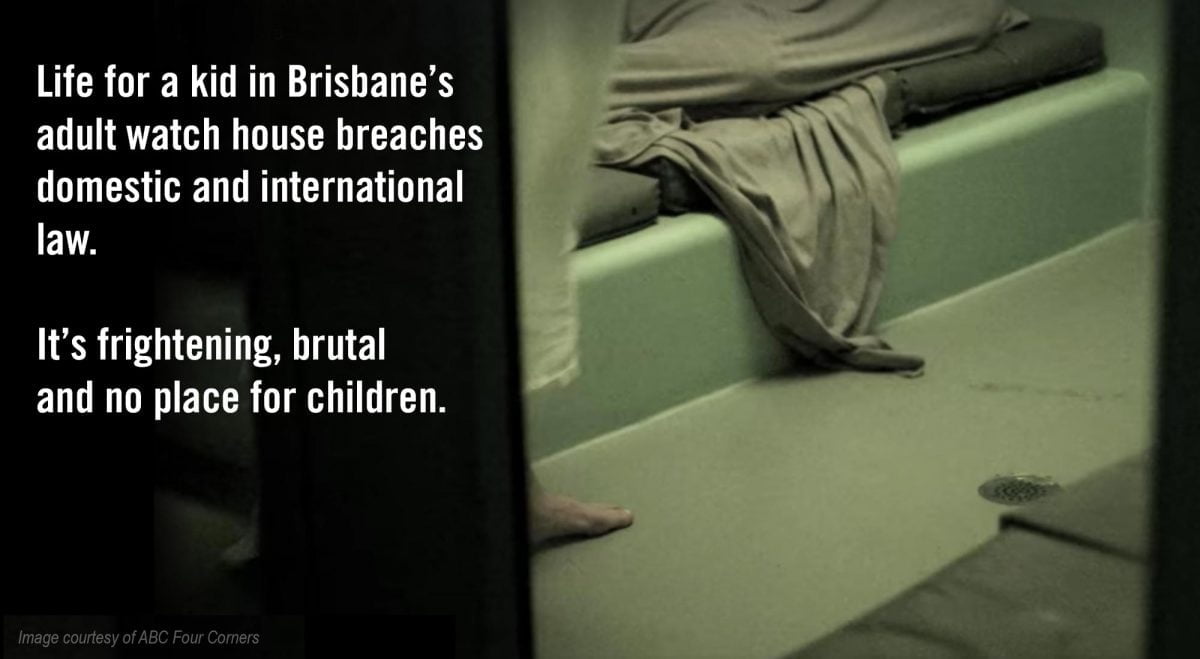

in the Brisbane City Police Watch House

Content Warning: contains descriptions of suicide, sexual harassment,

mistreatment and violence against children.

20 minute read

Amnesty International has analysed hundreds of official government documents obtained through multiple Right To Information applications. These documents revealed 2,655 breaches of international standards, Queensland regulations and the Queensland Police Operational Procedures Manual against children as young as 10 in the Brisbane City Watch House.

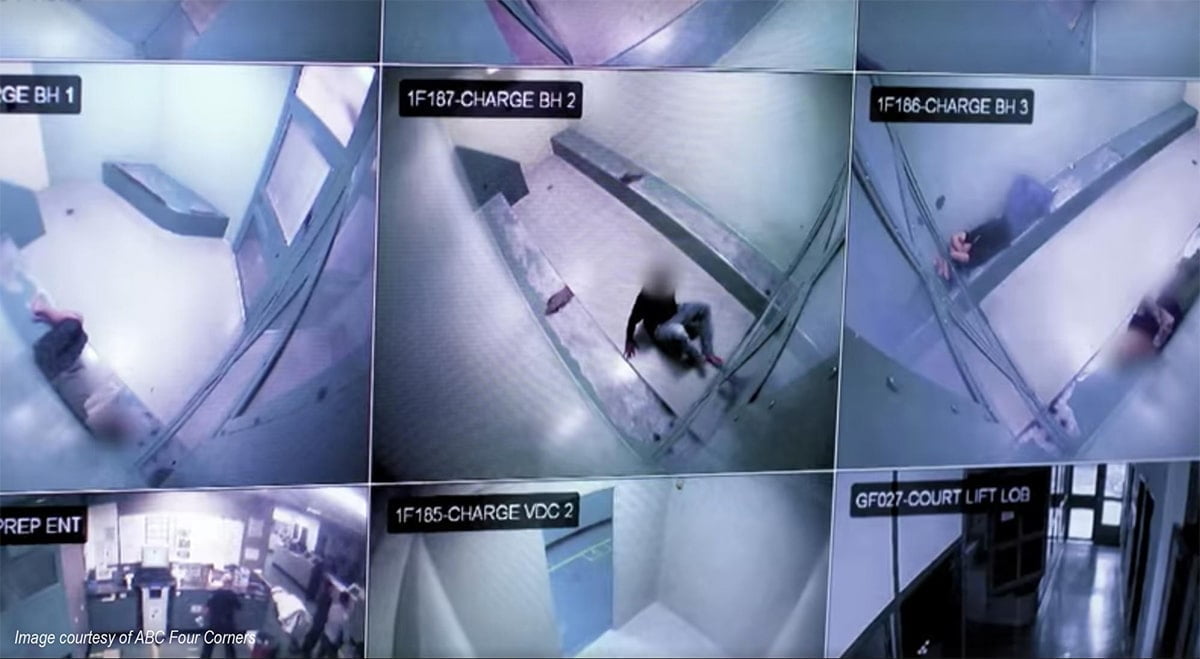

This information helped inform ABC’s Four Corners episode, Inside the Watch House: Kids behind bars.

As of 10 May 2019, there were 89 children in the Brisbane City Watch House, a facility designed to hold adults. At least half of these children are Indigenous and at least three were just ten years of age. One of the boys had been there for 43 days, despite Queensland law dictating no child may stay even one night in the Brisbane watch house. Four young girls were being held in isolation to protect them from other inmates.

Watch houses are built to hold adults for short periods of time after they are arrested, while they wait for their court hearing. They are staffed by police officers, and are generally attached to and run by police stations. They are not places children were ever meant to be kept in for even one night, let alone days, weeks or months.

The cells of the Brisbane City Watch House are very small. There is no direct sunlight. All a child has inside their cell is a wafer-thin mattress, and often no pillow. Each cell is designed for one person, but overcrowding means that kids are often locked up with another person, sometimes much older than them.

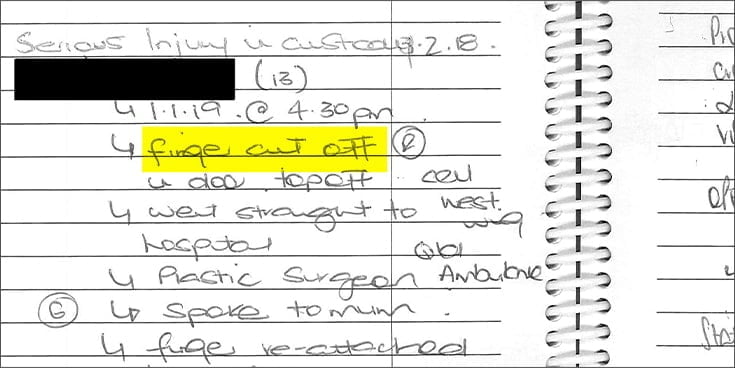

The documents Amnesty International gained tell stories of cell doors malfunctioning, closing on and, in one case, severing a child’s finger. Water fountains are covered in a green calcified substance, making them undrinkable. The design of the watch house means that children are sometimes kept in the eye-line of adult inmates, causing many children immense anxiety.

Why are children being held in

watch houses?

Watch houses are being used as a stop-gap to compensate for an at-capacity youth prison system and Queensland’s notoriously backlogged Children’s Court.

Of the children in Queensland prisons, approximately 86 per cent are currently ‘on remand’ — this means they are locked up even though they have not been found guilty or sentenced. And the situation is worse for Indigenous kids. They spend an average of 71 days in detention on remand, compared with 50 days for non-Indigenous children.

Kids were never meant to be in watch houses. Watch houses like Brisbane City are not properly resourced or regulated to care for children. While youth prisons in Queensland are held to account by the Youth Justice Act, the same laws do not apply to watch houses. For example, while a child in a youth prison may only be subjected to a half-and-half strip-search, the very same child may be completely strip searched by watch house police.

The government’s excuse for this lack of accountability is that children should only be held in watch houses temporarily, and never overnight, so those rights are not required — but we know from our investigation this is not the case.

THE EVIDENCE AND THE LAW

Holding kids for extended periods in watch houses that are not equipped to care for them has led to a serious human rights crisis.

Amnesty’s investigation uncovered 2,655 breaches of domestic and international law, including keeping children in watch houses for illegal durations; failing to provide children with adequate clean clothes, underwear and personal hygiene products; the institutional use of violence; the use of isolation as a form of punishment; failure to provide adequate health and mental health care; and failure to provide access to adequate education.

While the human rights violations detailed below come only from the Brisbane City Watch House, Amnesty has reports from organisations, children and families which confirm that the same things are happening to children in many of Queensland’s 326 other watch houses.

Children held for illegal durations without proper care

Amnesty obtained evidence of children being held in the Brisbane City Watch House for days, weeks and even months. We also uncovered evidence of poor resourcing, including not providing adequate clean clothes, underwear, shampoo and conditioner, and an instance of police telling a child to choose between clean clothes and a phone call to family.

On 14 November 2018, Jake* spoke to a Community Visitor about his stay at the Brisbane City Watch House (*his name has been redacted to protect his identity). At that point, he had been held in the watch house for 20 days. During his stay, he was not given fresh clothing (a common complaint from children in watch houses) and had very little fresh air in his cell. Jake was yet to access any education services, while his classmates continued to learn and play outside the watch house. Despite not being due in court until 9 December 2018, he did not know when he would be released or transferred to the Brisbane Youth Detention Centre.

Amnesty received proof of the complaint the Community Visitor made after speaking with Jake. Community Visitors are independent representatives who speak to children in the care of the state to ensure that their welfare is properly protected.

Unfortunately, Jake’s experience is not uncommon for children in Brisbane’s watch house.

In November 2018, a 12 year old girl, Amy*, was brought in and held for nine days before finally being transferred to the Brisbane Youth Detention Centre. Email correspondence suggests that during her time there, she was harassed by boys in the watch house, and was never given shampoo or conditioner. When investigated, the watch house nurse said that while they had head lice treatment shampoo, there was no other shampoo available.

Amnesty encountered many stories indicating the poorly-resourced nature of Brisbane City Watch House.

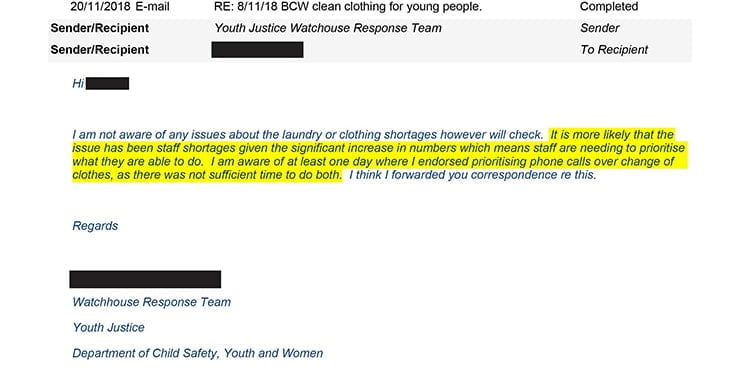

Grant*, a 15 year old boy had been at the Brisbane watch house for 20 days when he told his Community Visitor that he wasn’t being given enough clean clothes. He received a clean tracksuit just every two days, and clean underwear even less regularly. When he made a complaint to a police officer, he was told, “Do you want clean clothes or a phone call?”

After speaking with youth workers and other watch house staff, the Community Visitor discovered that there were not enough clothes to go around.

Amnesty received this email exchange between the Community Visitor, and a member of the Watchhouse Response Team. In it, the Manager explained:

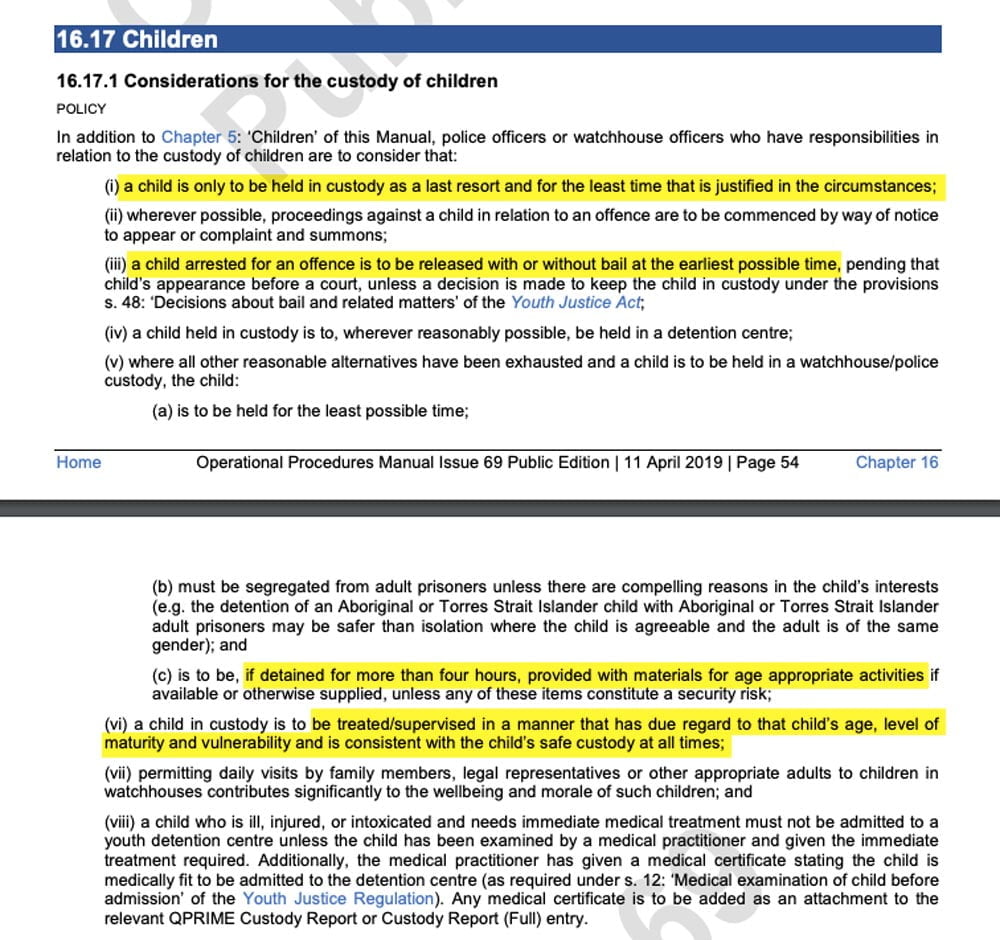

Queensland, and indeed, international law, is very clear when it comes to the incarceration of children. The Queensland Police Operational Procedures Manual states clearly that Brisbane City Watch House is a watch house where, “subject to reasonable operating resources at the time, children are never to be kept in custody overnight…”

Beyond mandating that “a child is only to be held in custody as a last resort and for the least time that is justified in the circumstances,” the Manual also states:

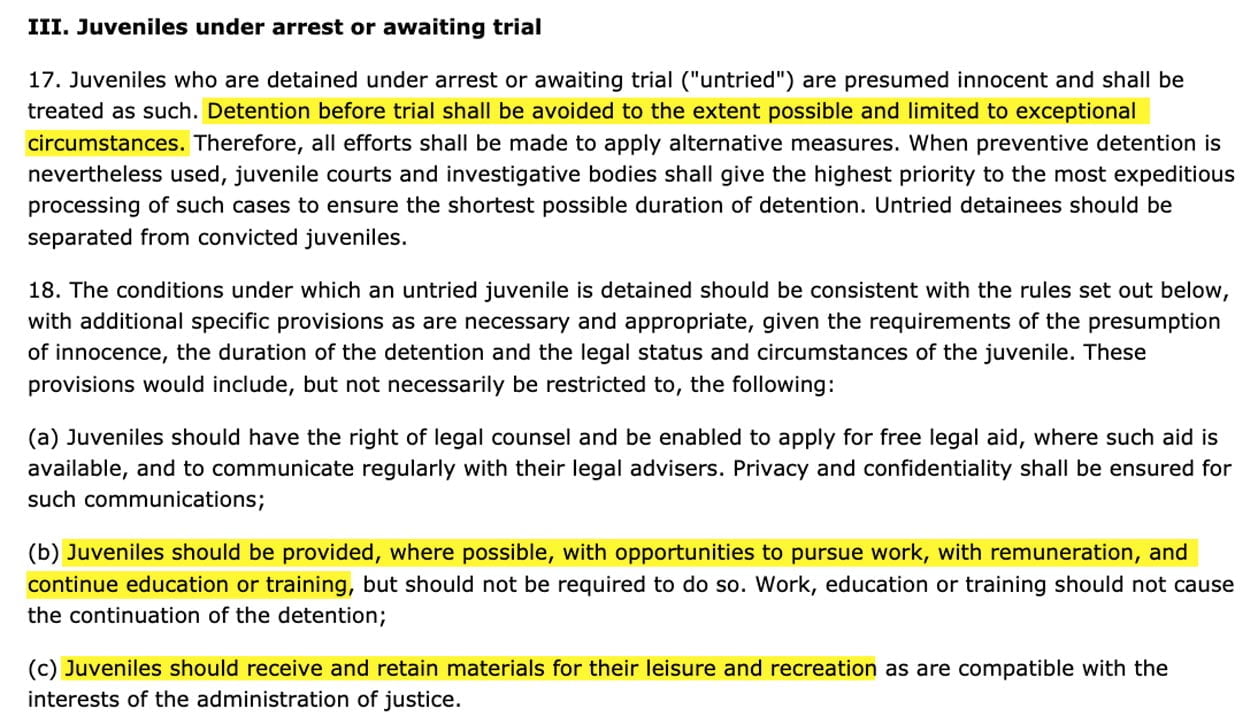

The international standards for detaining children are established in the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty, known as the ‘Havana Rules’. They clarify that the detention of juveniles, should be “limited to exceptional circumstances”, they should be “given the opportunity to continue education”, and should “receive and retain materials for their leisure and recreation”.

What the law dictates is a far cry from the poor treatment Jake, Amy and Grant received in November 2018. The law reminds police that children should be treated as children, that a cell is no place to keep a child, and that all efforts should be made to protect them from harsh, toxic environments.

It’s simple: the commonplace detention of children in Brisbane’s police watch house breaks Queensland law, and international human rights law.

Children subject to institutional violence

Amnesty found evidence of institutional violence in watch houses. Where children must be incarcerated, they must also be protected from any violence, especially by police officers and other inmates. Even one instance of police brutality against a child should be cause for serious alarm.

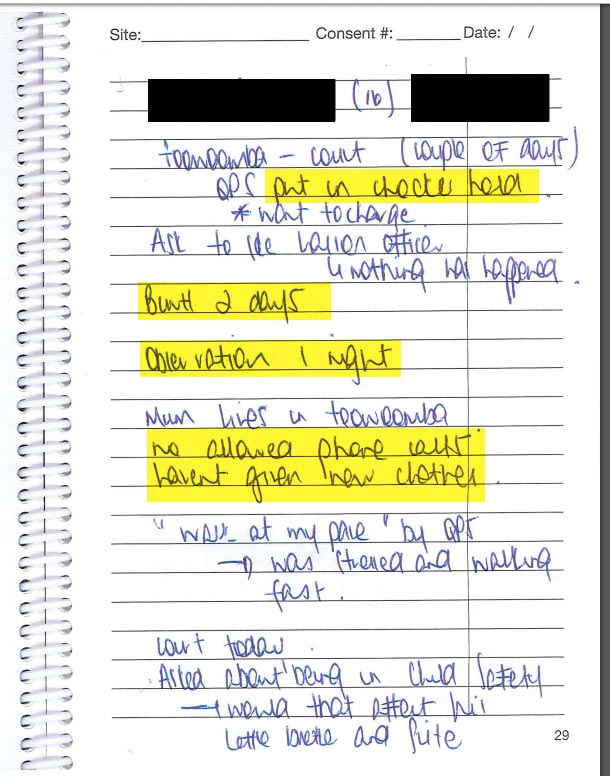

When Tom*, a 16 year old boy, left Toowoomba Court for Brisbane City Watch House, he reported feeling stressed — a natural response to an intense environment. As he walked, he was accompanied by a police officer. He walked quickly, because of his discomfort. The officer told him many times to “walk my pace”, however Tom did not comply — he was understandably stressed, anxious and uncomfortable. Following this, the officer apprehended Tom, putting him in a choke hold from behind. According to a record of the events, Tom nearly passed out.

Tom complained to a Liaison Officer in the watch house. There was no response. At the time of his interview with a Community Visitor, he had been there for two days. He was also being held in isolation. Like many others, he was not allowed any phone calls, or offered a change of clothing during his stay. As can be seen from a Community Visitor’s personal notes, he asked for an official complaint to be made on 28 November 2018.

Children in watch houses are supervised by police officers who have not been trained to work with children. This goes some way to explaining experiences like Tom’s and many others’. Police watch houses are sanctioned to use more force than youth prisons — and are able to carry out invasive and complete strip searches.

Even police officers themselves are aware that they are not the right people to look after kids in detention. Queensland Police Union president Ian Leavers said in February 2019 that “Police have had enough. We are not babysitters for juvenile offenders.”

Amnesty found several other instances of excessive force used against children. One young person was allegedly “smashed against a wall and floor” by Queensland Police staff. Another young person reported having a mouth swab taken by staff without warning, consent, or explanation, before being put into handcuffs.

Children kept in damaging isolation

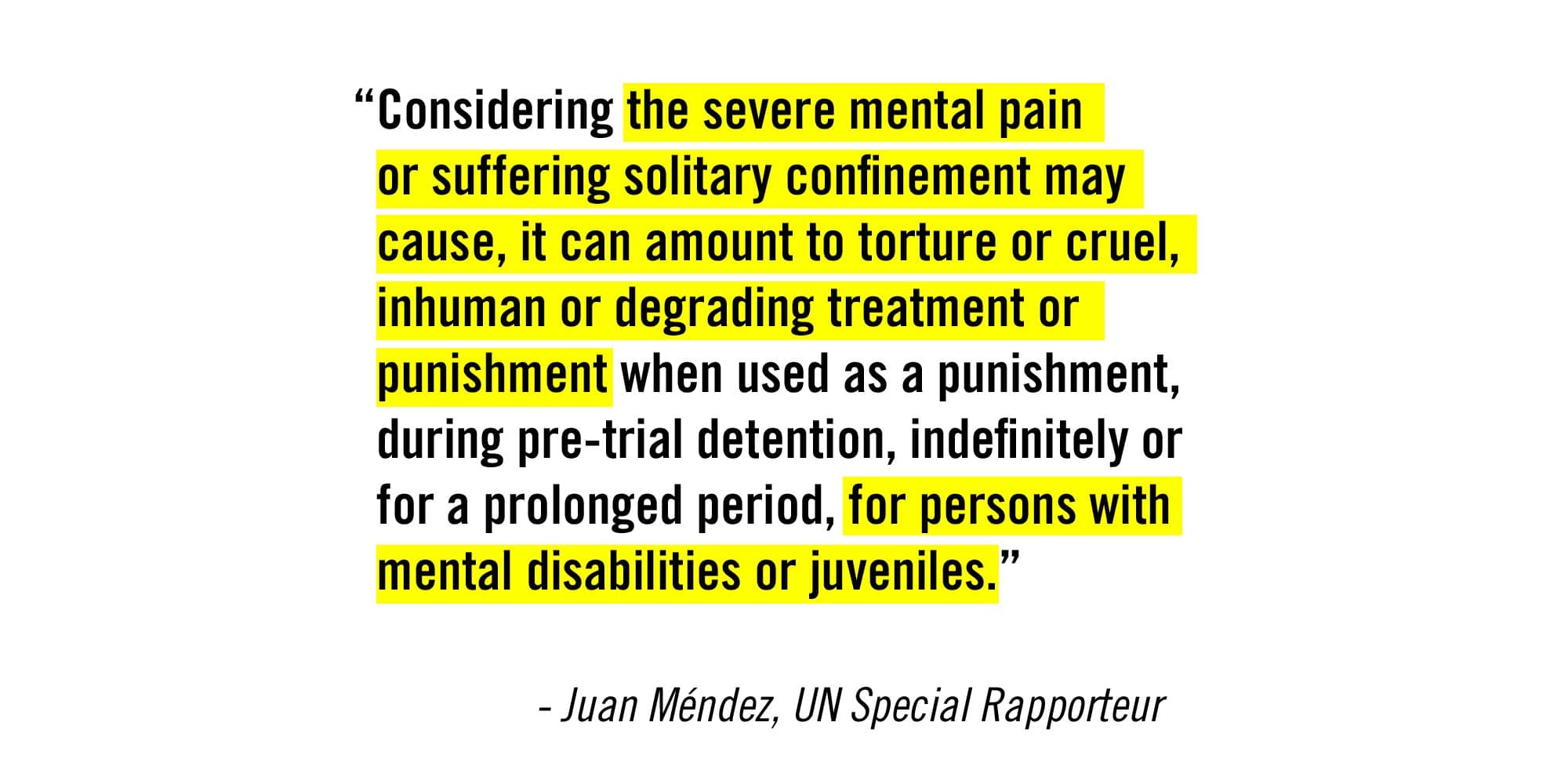

Amnesty uncovered what appears to be common use of isolation as a disciplinary method. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture has been very clear on the isolation of children: it should be banned.

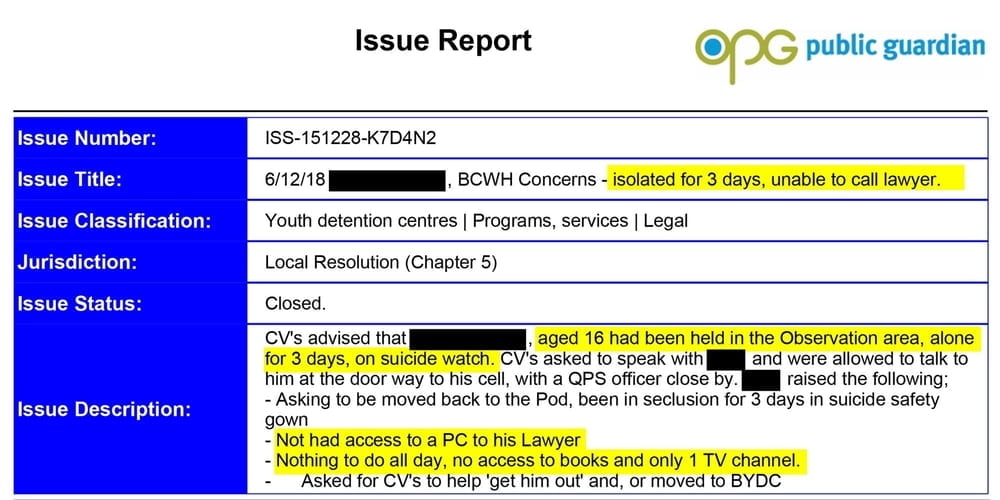

When a Community Visitor spoke to Sam*, a 16 year old boy, he had been isolated in an observation area for three days on suicide watch. With no books and only one TV channel, his time had been particularly isolating. Rather than police being properly trained in how to work with suicidal children, they put Sam in a suicide safety gown — a hospital-style smock designed so that the wearer cannot use it to commit suicide. He had not been given any means to contact a lawyer, despite directly communicating to the Community Visitor that he wished to be placed back in his cell or moved to a youth prison.

Only after Sam spoke with the Community Visitor was he finally given a book to read and a phone to contact his lawyer. He was transferred to Brisbane Youth Detention Centre later that day.

Isolation is frequently used for people like Sam: already under immense psychological stress and identified as suicide-risks. Isolation often inflames ongoing trauma, as kids are left to their own devices, only able to interact with police officers who themselves may be sources of trauma.

Isolation is also commonly used for girls, who under international law — specifically, Rule 8a of the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners — should be detained separately to boys and men. The floorplan of Brisbane’s watch house does not allow for this and girls are often held in the eye-line of people, including men, who are much older than them. As such, the ‘best’ police can do, is put girls into isolation.

Limited access to health care and mental health support

Many of the children who enter watch houses like Brisbane’s suffer from intergenerational and childhood trauma and consequently poor mental health. Many find that their health continues to suffer once in their cell.

Amnesty’s investigation uncovered that, in the last 12 months, there were at least three suicide attempts made by children in the Brisbane watch house, and several more children such as Sam were put on suicide-watch. The suicide safety gowns they are forced to wear are degrading and cannot be worn with underwear.

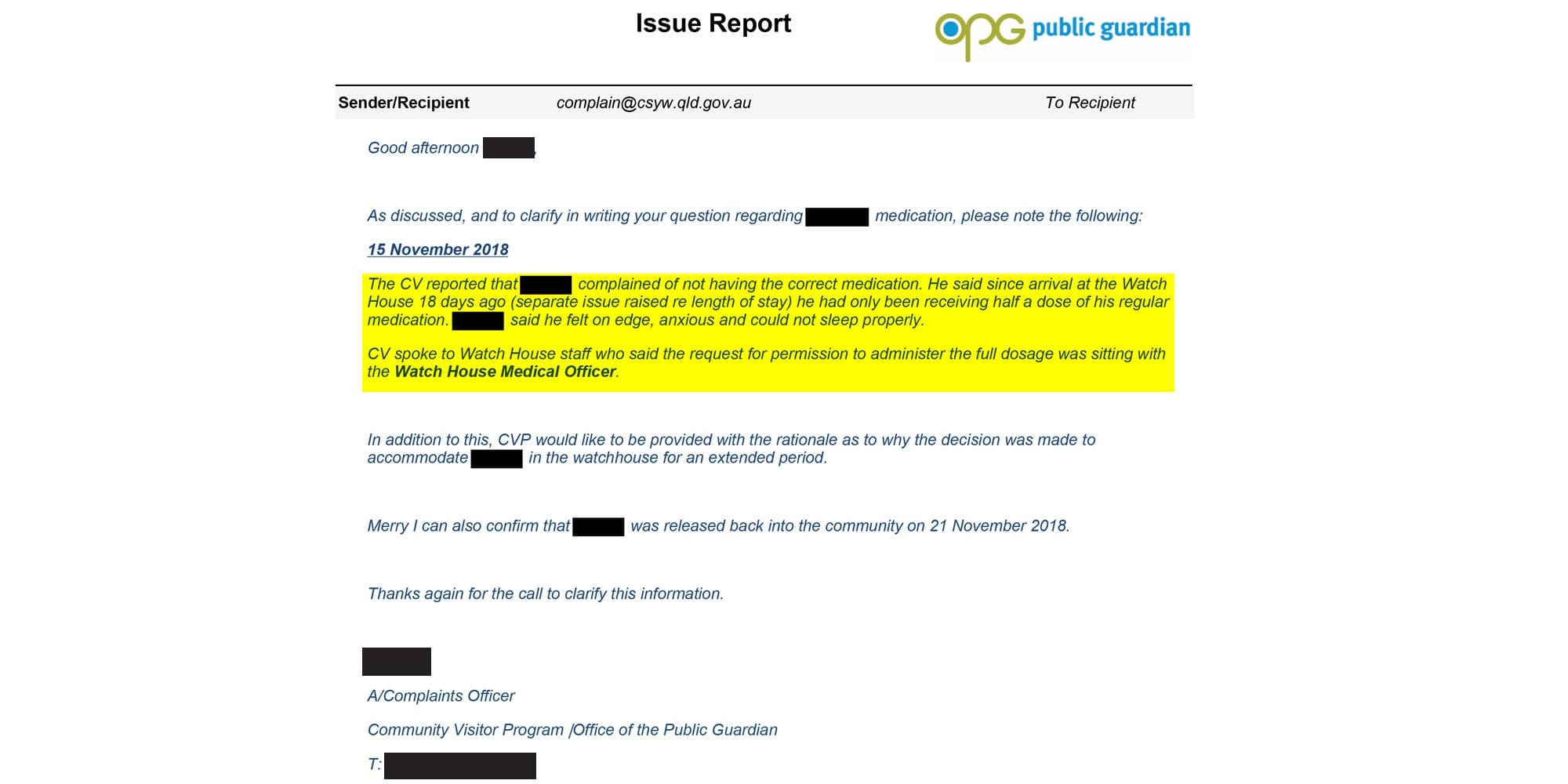

Amnesty also uncovered stories of children suffering as a result of not having the correct medication. During a child’s stay, the police officers at the watch house and the supporting medical officers are solely responsible for the proper delivery of medication.

Grant* spoke to a Community Visitor after 18 days of incarceration in Brisbane watch house. Grant complained that during his stay, he had only been receiving half a dose of his regular medication. Because of this, he felt on edge, anxious and could not sleep properly. Once the Community Visitor communicated his complaint to watch house staff, they admitted that the request for permission to administer the full dosage was sitting with the watch house medical officer.

Other complaints include an asthmatic child without a puffer, children suffering from substance withdrawal and requesting to be taken into rehabilitative-care, and several complaints from children feeling their mental welfare was suffering because they were being given too little food.

Limited access to education

Amnesty obtained emails between the Queensland Department of Education and teachers working with incarcerated children that show Brisbane City Watch House is failing to enforce children’s right to education.

The Queensland’s Youth Justice Act (not enforceable in watch houses) mandates that all incarcerated children be given proper education, so that their incarceration assists their rehabilitation, rather than obstructing it. This is supported by the ‘Havana Rules’, which set out international standards for the treatment of incarcerated children.

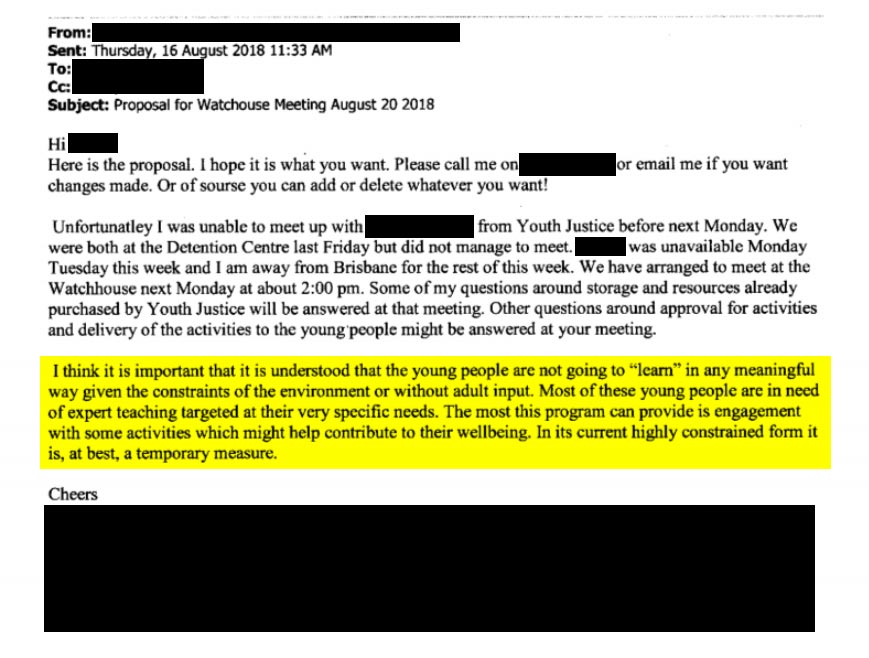

Sarah*, a teacher, made a complaint to the Department of Education regarding the quality of education being delivered in the watch house. Having been unable to meet with her student once she was at the watch house, she emailed the Department, explaining her broader frustration with the program.

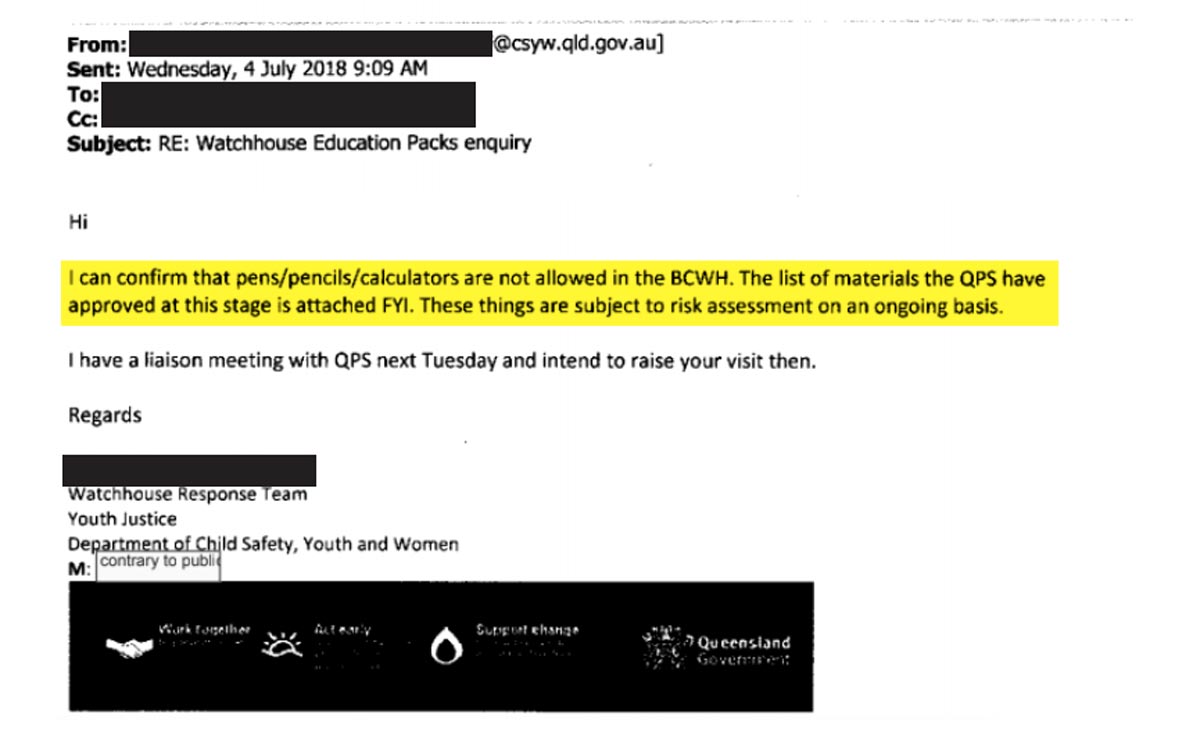

In another email, a member of the Watchhouse Response Team from Youth Justice confirms to the Department of Education:

In response to Sarah’s email outlining her concerns, the Department of Education thanked Sarah for her efforts, but explained that her suggested reforms were not possible. Their explanation was that given a “watch house is a temporary basis and for short durations as the young person will transition out as soon as possible”, it would not be feasible to provide more substantial educational programs.

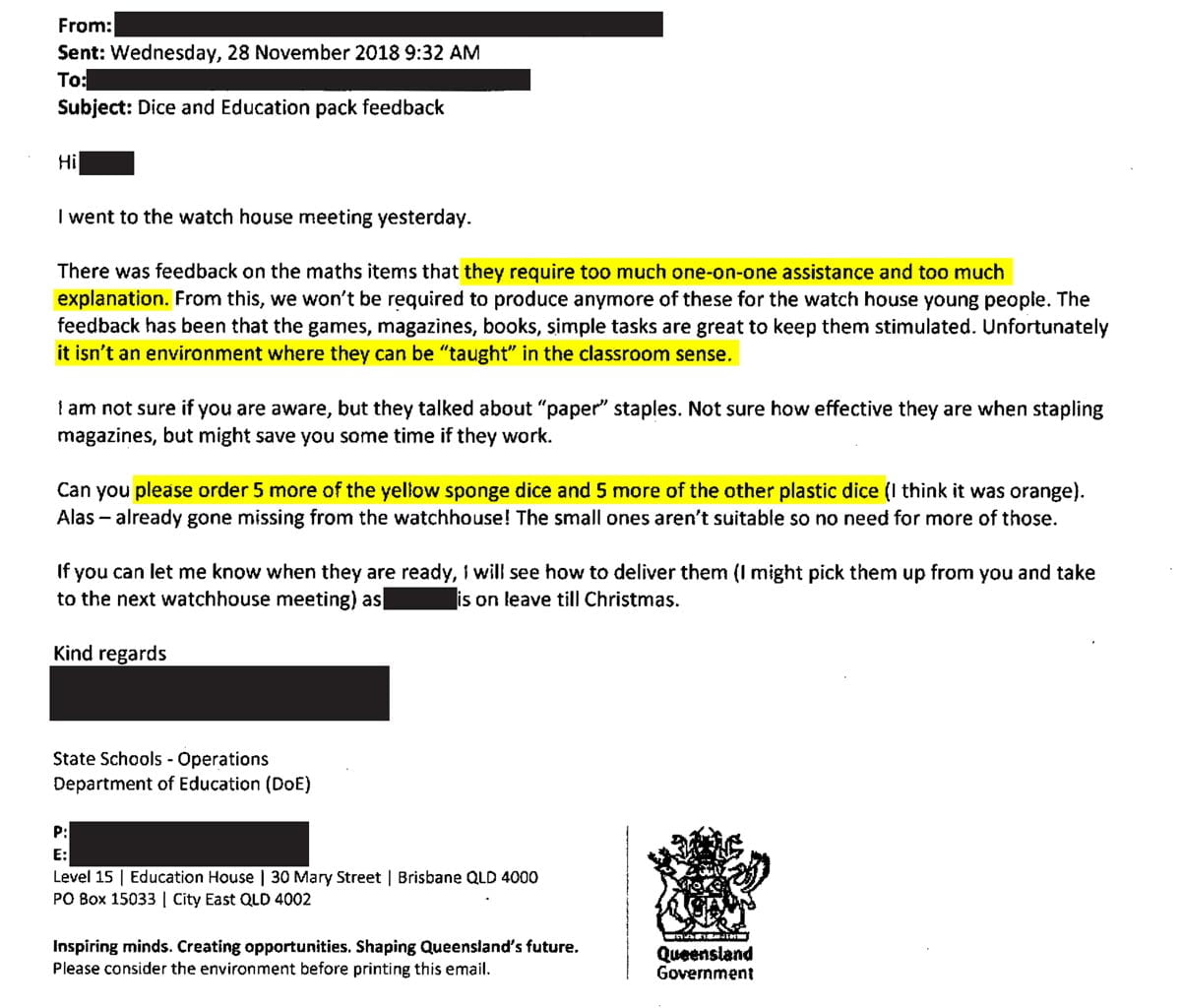

In another email, the Department of Education justifies the removal of maths items from the facility because “they require too much one-on-one assistance and too much explanation.” Instead, the Department felt that “five more of the yellow sponge dice” and “five more of the plastic dice” would suffice.

While the Department claims that they are not required to provide properly resourced education programs due to the intended temporary nature of watch house incarceration, we know from our investigation that children are being kept for much longer durations.

The impact of trauma on kids development

What is the effect of all these human rights violations on the children that endure them?

Amnesty International’s Sky Is The Limit report details the compounding negative impact prison has on a child’s brain development:

“Toxic stress or trauma can have a negative impact on brain development. Examples of toxic stress include: exposure to violence or abuse, neglect, lack of affection, parental mental illness, poverty, removal from family, and placement in a prison environment. Indigenous children are more likely to experience trauma than their non-Indigenous peers because of the cumulative effect of historical and intergenerational trauma, which can all be traced back to colonisation.”

“Prison is not an environment where children can flourish and grow up strong and healthy. Instead it’s a place which compounds existing issues children face or creates new mental health, social, emotional and wellbeing problems.”

“A 2014 Victorian study of children in prisons found that 39 per cent had symptoms of depression, 17 per cent had a positive psychosis screening and 22 per cent had engaged in self-harm in the past 6 months. A NSW study found that 83 per cent of children in prison had a psychological disorder, 60 per cent had experience of abuse and 70 per cent had a behavior or attention disorder. The 2016–2017 Northern Territory Royal Commission found that the conditions children were placed in, including those meant to manage at-risk behaviours, exacerbated the distress of children in prison rather than preventing serious harm.”

The impact of Amnesty’s investigation so far

Following the results of our investigation, on 26 February 2019 Amnesty wrote to Queensland’s Minister for Child Safety, Di Farmer. In the letter, the National Director of Amnesty International, Claire Mallinson, outlined the human rights breaches being committed by the Brisbane City Watch House, and called for an end to the violations. We gave specific directions for what changes the Queensland Government must make to protect incarcerated children. These were :

- immediately release all children on remand back into the community and/or with family, where safe to do so, and work with the Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women, to find accommodation for those who need it;

- significantly expand Supervised Bail Accommodation Services in Queensland as soon as possible, to reduce the significant remand rates causing overcrowding at detention centres;

- legislate to uphold Appendix 16.8 of the Queensland Police Operational Procedures Manual as soon as possible; and

- legislate to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility to at least fourteen years of age.

In response on 30 April 2019, Minister Farmer announced the Queensland Youth Justice Action Strategy — which included $320 million to reduce the number of children on remand. Amnesty welcomed “the prevention and early-intervention elements of the package, particularly the commitment to expanding Queensland’s restorative justice program, and a ‘transition to school’ program.”

However, much of the strategy is geared towards moving children from watch houses to youth prisons, with $177 million to go towards building more beds in youth prisons. Amnesty opposes this part of the strategy – no solution that promotes the continued incarceration of children is a viable one.

The serious lack of transparency surrounding watch houses in Queensland means the full extent of the problem is not known. Amnesty has been able to learn much about Brisbane City Watch House, but there are 326 other police stations in Queensland capable of ‘temporarily’ holding children. To best protect Queensland’s children, the government must allow more transparency, reporting and accountability with regards to how they incarcerate children.

Solutions

Keeping children in watch houses, or any form of incarceration, starves them of a childhood. It deprives them of community-based rehabilitative initiatives proven to be more effective at caring for children.

Tammy Solonec, a Nigena woman, lawyer, and the Indigenous Rights Lead at Amnesty International, explains why Indigenous-led solutions are so crucial in reforming the justice system.

Neither watch houses, nor youth prisons are places for a child to spend their childhood — they deserve to be in a classroom, with their friends, family, and community.

We must support community-led solutions to keep children out of incarceration. However, we also need governments to do their part and enact institutional reforms.

- More investment in prevention and diversion – especially with Indigenous-led programs

Support must be given to Indigenous-run programs that help Indigenous youth so that they are less likely to be incarcerated or re-offend. Queensland’s youth justice system has multiple diversionary services, and yet in 2016-17, only two of the 16 services were run by Indigenous-controlled organisations. The Government must support autonomous organisations, who provide youth offender support services, community accommodation, employment project officers and specialist counselling services. Prevention and diversion approaches and programs are critical in order for Australia to fulfil its obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other applicable norms and standards under international law – especially the fundamental principle that detention should be a last resort for children. - Legislate to increase the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14

Across Australia, children as young as 10 can be incarcerated in either a watch house or a youth prison. Australia is out of step with the rest of the world by allowing such young children to be locked up. All Australian governments must immediately raise the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14 years of age, with no limitations for children under this age regardless of the crime, and transition all children under 14 out of prison within a year. - Legislate to uphold Appendix 16.8 of the Police Manual, to ensure that the Youth Justice Act extends to all incarcerated children in all remaining situations

Watch houses should never be used to hold children. Appendix 16.8 of the Police Manual specifies the watch houses that children should never be held in, including Brisbane City Watch House. The Queensland government must immediately legislate to uphold Appendix 16.8, to ensure that the Youth Justice Act extends to all incarcerated children in all remaining situations. - Urgently investigate why there are so many children in Queensland held on remand and make changes (including to the Bail Act) as required

A large cause for the 86 per cent of Queensland’s incarcerated children being on remand is the inefficiencies in the bail system. The Queensland government must urgently investigate these inefficiencies, so that we avoid the situation of young children being held, unsentenced, for over 40 days in a watch house, like the case study above. - Invest in supervised bail accommodation

Government must also support Indigenous communities and autonomous, community-led justice solutions. Queensland and other jurisdictions must invest in Indigenous-run bail houses as an alternative to youth prisons. Instead of being watched 24/7 by police or youth officers, they will be cared for by community members they very well might already have relationships with. Children avoid the trauma and criminalising effects involved with a prison environment, and are able to have as close to the normal childhood as possible. This has been recommended in the Atkinson Youth Justice Report.

Take Action Now

Children do not belong in police watch houses or youth prisons. They need to be with their families and communities so that they have the best start to life possible. Sign the petition to help pressure the Queensland Government to remove children from its watch houses.

Have your own story about watch houses from anywhere in Australia? We need you to help us hold governments to account so that every child can grow up in safety, surrounded by family, friends and community.

Please contact us at joel.clark@amnesty.org.au – we will keep your information confidential, but may be in touch for further information.

Contributors

Amnesty International would like to thank the many Amnesty International staff, activists, caseworkers and interns who contributed to the research behind this campaign to get children out of watch houses. For their many hours of Right To Information research and analysis, thank you to: Belinda Lowe, Mary Morrison Roth, Sehar Ashar, Zoe Neill, Meg McLellan, Valentine Dubois, Chloé Tremblay-Goyette, Cailey Campbell, Morgan Somerville and Sam Radford. For his outstanding effort to turn our research and legal analysis into an important and powerful story, thank you to Liam Thorne. For sharing their stories and experiences, thank you to the many children and families who spoke to us.

Artwork created by Emma Hollingsworth, a proud Kaanju woman and contemporary Indigenous artist. Find her as Mulganai on Instagram.