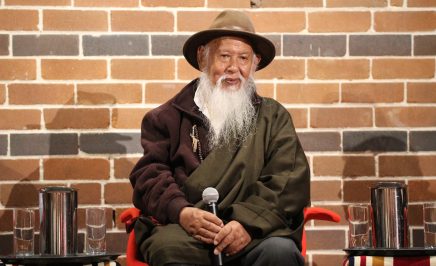

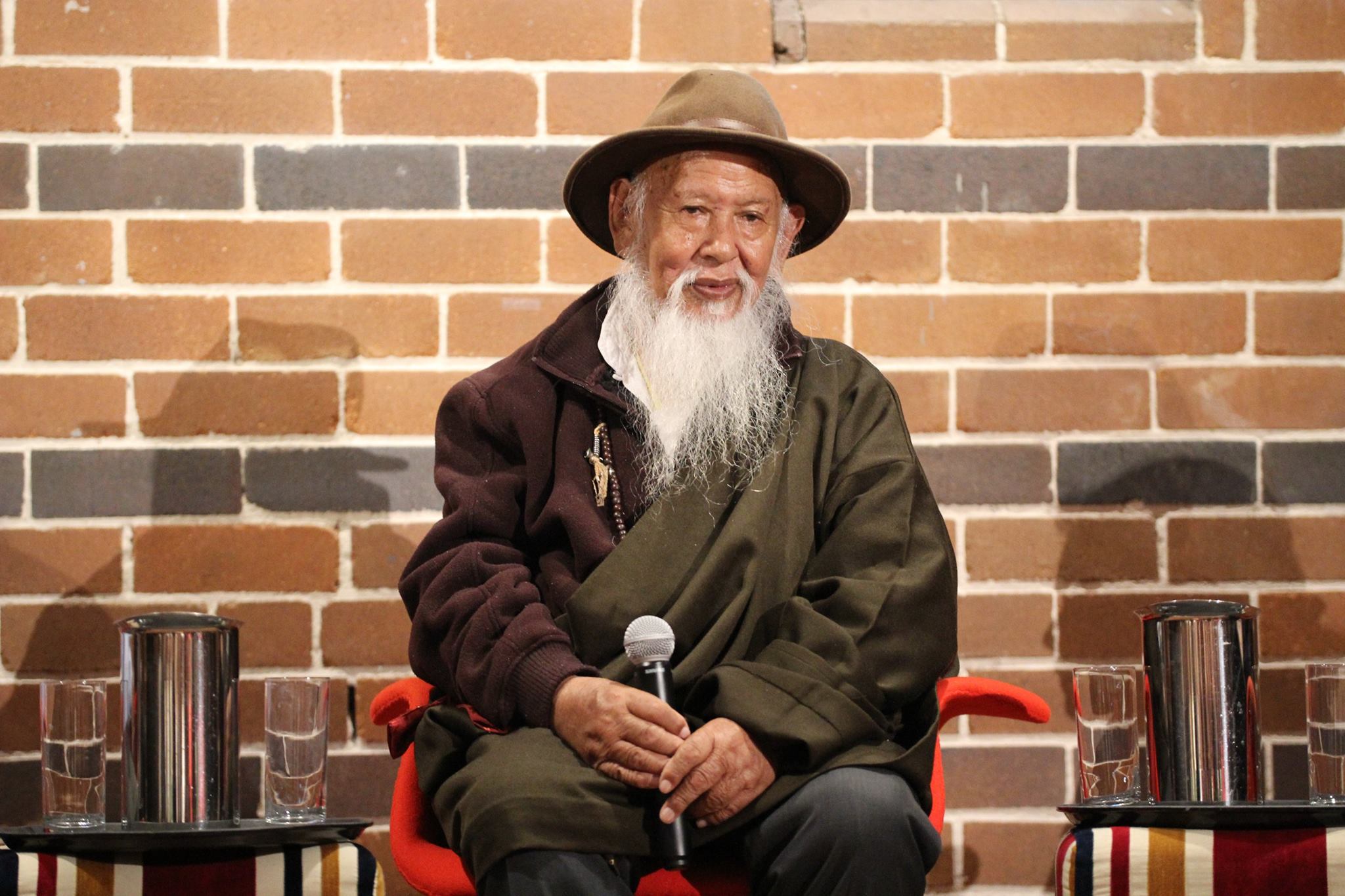

I was born in a farming family in a small town near Lhasa in independent Tibet. The year was 1934. Most Tibetans were farmers and nomads who have lived in harmony with our natural environment for many generations. We shared a deep connection to the land, the rivers and the mountains.

Tibetans are mostly Buddhists. There is a small number of followers of Bon, Tibet’s indigenous religion before Buddhism came to Tibet in the 7th century. Buddhism is an integral part of our culture. Most families would send at least one son to the monastery. I became a monk at the age of six.

When I was in my late teens, I heard about communist Chinese troops entering Tibet’s eastern provinces bordering China. The Chinese told the Tibetans that they were coming to help us, to modernise our country. Many did believe them at first. But soon they destroyed our monasteries, took control of our resources, arrested our leaders and ruled us.

I joined the resistance movement at the age of 25. For that, I spent 24 years in prison. After my release, I fled into exile to live close to His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala in northern India.

Few years ago, I was given a humanitarian visa to Australia. From the mountains of Tibet to the Northern Beaches of Sydney, I have come to share the suffering of my people and seek justice.

You took part in the uprising in Lhasa on 10 March 1959? How has that day shaped your life?

The Chinese military began invading eastern Tibet in 1950, a year after Chinese Communist Party came to power in Beijing. The Tibetan leaders tried to settle the conflict during the early years of the invasion, to no avail.

By 10 March 1959, the Chinese military had besieged Lhasa. That day, a huge crowd of Tibetans surrounded Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s summer palace, and marched on the streets to protect our leader. Rumours had spread that the Dalai Lama was going to be arrested that day. This marked the beginning of the uprising in Lhasa and a military crackdown by the Chinese authorities.

We held an urgent meeting at our monastery that night. I signed up to join Chushi Gangdruk, a guerilla group that had started in eastern Tibet in 1956. Literally meaning Four Rivers, Six Ranges, Chushi Gangdruk is also known as Defend Tibet Volunteer Force. Little did I know when I became a monk as a young boy that I would one day join an armed resistance group. For us monks, it was our duty to protect Buddhism from the communist Chinese.

As violence ensued in the following days, a young Dalai Lama had to make the most difficult decision to leave his homeland and escape to India from where he could appeal for international help. On 17 March 1959, he left his palace, disguised as a Chinese soldier and crossed the mountains. Two days later, the Norbulingka Palace was heavily bombarded by Chinese troops. I vividly remember the incessant shower of bullets and the piles of dead bodies strewn everywhere. It was unimaginable.

The Tibetans were too ill-equipped and untrained to resist the Chinese troops. We had rifles; they had machine guns. But we did not give up and put up a good fight for a few more days and went to two other towns near Lhasa, defending our monasteries which were coming under heavy attack. In late March, I was severely wounded and captured.

Tell us about the time you spend in prison for 24 years.

After my arrest, I was put in solitary confinement at my monastery for six months. I was tortured and forced to confess guilt over my actions and disclose the names of my accomplices. When I refused, I was sent to a prison to be “reformed”. Thus began my 24 years of imprisonment and torture.

Food was scarce in prison. We would go without food for days and would end up eating grass. Many fellow inmates died of starvation. Once I saw a monk quietly chewing on something. I asked him what he was eating when others were dying of hunger. He had found bones of dead prisoners.

He shared some with me on the condition that I didn’t tell anyone. In any case, I would not brag about eating human bones. The prison guards learnt what we were doing and threw the bones away.

Whatever food we got was not enough as we were working 12 hours a day at construction sites. From the early days of occupation, the Chinese government started building dams on Tibetan rivers, using prisoners as labourers.

All the big rivers of Asia, including the Yangze River and Yellow Rivers in China, start from Tibet. These dams are built to generate electricity for Chinese cities, without local consent. Such big dams are bad for Tibet’s fragile environment. China invaded Tibet to take control of our waters and natural resources, of which we have had plenty. Gold, copper, lithium, iron ore, aluminium, and so on.

In prisons, “political education” sessions were a big part of our daily routines, during which we were forced to denouce the Dalai Lama and sign a confession statement stating Tibet is a part of China. Those who obliged would be released from prison. I refused as the Chinese government would use these statements to legitimise their rule. They punished me with a seven-year prison term and stripping of political rights for a lifetime.

I was then moved to another prison Drapchi, Tibet’s most notorious prison. Prisoners were dying from torture and undernourishment there. When fifteen people lost their lives one day, the prison authorities launched an inquiry. They summoned me for interrogation. They claimed there was an outbreak of a disease, but I knew that was not the case. I openly criticised the Chinese government’s policy and accused them of ethnic cleansing.

The Chinese government was killing our people, our history and our religion and culture. In prison, we were forced to urinate on sacred Buddhist textbooks. As a Buddhist monk, it was the most painful thing to do. Having seen many dying in front of my eyes, I was counting my days and was not afraid to speak up.

Towards the end of my seven-year prison term, prison officials showed us a Japanese movie depicting the cruelty of Japanese imperialist rule and how Chinese children were separated from their parents for many years. During the discussion on the film, I accused the Chinese of doing the same thing to the Tibetans. I pointed out that I had not been allowed to meet my parents during my imprisonment.

Few days later, my mother was brought in to see me. They told me I would be released if she expressed her regret over my actions and her gratitude to the Chinese Communist Party for the prosperity it has brought to Tibet.

My mother refused to give in and told me to continue to fight. So the Chinese authorities extended my sentence and I ended up spending 24 years in prison.

I spent many months in solitary confinement at Drapchi. The only contact with humans were with prison officials who interrogated and tortured me every day. When I refused to give in, I was beaten up by angry guards. My legs were broken. To this day, I can’t walk without assistance.

In the early 1980s, the leadership in China changed which gave some hope of China opening up. One of the leaders Hu Yaobang believed political reforms were neccessary in China and even showed some sympathy towards the plight of Tibetans.

In 1982, I appealed to the Chinese authorities to release me for my good behaviour in prison and for the fact that I was one of the longest serving prisoners. On 1 December that year, I was released from prison. It felt like a miracle. I never imagined during those 24 years that I would one day walk out of prison, go to India, meet the Dalai Lama and eventually move to Australia.

I am turning 90 this year, and as I look back, have no regrets of spending all those years in prison. I stood up for justice. My legs are not great. But my spirit is still strong. I may not get to return to Tibet but every morning I pray for world peace and for the Dalai Lama’s final return to Tibet.