“It’s that time of the month.” “Red October.” “On the blob.” Many people would rather call menstruation anything than what it is. But in parts of the world the stigma around menstruation goes far beyond euphemisms. For some girls, menstruating means being hidden away in cattle sheds or banned from their houses; others struggle to afford tampons and pads and are forced to make do with rags. Some women have even been arrested or interrogated for their peaceful activities to change this stigma.

Yet things are starting to change. We spoke to five brilliant human rights activists breaking the taboos surrounding menstruation.

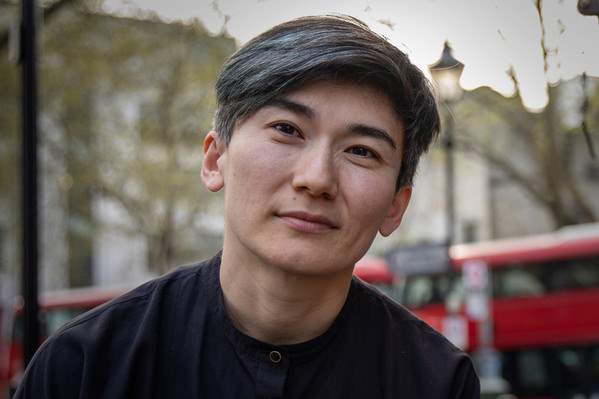

Zhanar Sekerbayeva, 36, Kazakhstan

LBQ activist and founder of ‘Feminita‘

In Kazakhstan, we’re still unable to call menstruation what it is. Instead, people use euphemisms such as Red Aunty, Red October or Red Army. My mum is a paediatrician and when I had my first period she threw me a piece of cloth, without explaining what it was for or how to use it. Some people bury their bloody panties outside, while others use contaminated rags, causing reproductive damage.

“At school, if a girl’s period leaks onto her clothes, everyone laughs, and her teacher will send her home.”

Something needs to be done. That’s why I joined a group of peaceful protestors in Almaty, Kazakhstan, to participate in a photo shoot aimed at tackling the taboos around menstruation. We took hand-drawn posters with slogans and pictures. After the demonstration I went to a café and when I came out, seven policemen were waiting for me. They ordered me to go to the station and said if I didn’t, they’d use physical force.

I was charged with minor hooliganism. I was interrogated by a judge and she questioned me endlessly about the poster I was holding. She also asked questions like “Are you married? Do you have any children? Are you pregnant?”

I told her I was an open lesbian and to question me about a partner, not a husband. It was an interesting experience, albeit a stressful and scary one, but when I see people facing injustice, I have to act.

Hazel Mead, 23, UK

Activist and illustrator

The UK is more progressive than many other countries, but growing up I always felt shame about my period. I think this is because periods weren’t talked about at school and, when they were, they were referred to with a plethora of euphemisms – ‘that time of the month’ was mine. It also wasn’t something you’d discuss with men, which adds to this idea that menstruation is this big shameful secret. At school, in jobs even, I would hide a pad up my sleeve or make sure I was wearing pockets on period days.

I use illustration to start conversations about and normalise periods. Near the start of my career I started creating satirical pieces about the tampon tax after attending the #FreePeriods protest. I volunteer my drawing skills to Bloody Good Period frequently, as their work to ensure asylum seekers and homeless people have access to period products is something I completely believe in. I was also part of Freda’s campaign to get hotels, schools, airlines and offices to provide free period products. In my personal life I am also talking about my period more. I no longer use euphemisms, and call pads and tampons ‘period products’ rather than ‘sanitary products’, which implies that periods are unclean.

“This year the UK government announced it would provide free period products in secondary schools and colleges in England from the next school year. This wasn’t my doing, but I have been part of this movement behind all the campaigning for change. There is still so much to be done to break menstrual taboos and injustices, but little by little as we keep making noise, we’re seeing change.”

Samikshya Koirala, 21, Nepal

Youth Executive at Amnesty International Nepal

In Nepal, girls who are menstruating can be hidden away from the sun and from men for up to 15 days. Some girls are even exiled to cattle sheds – it’s a tradition known as ‘chhaupadi’.

I was 11 when I had my first period. A grand event was taking place at home, but I wasn’t allowed to go because I was menstruating. Instead I was hidden away in a dark room at a relatives’ house, far from my home. I was really looking forward to the event and I cried until my eyes were swollen.

I was hidden away for five days. After I came out, I wasn’t allowed to touch the male members of my family for 11 days or go into the kitchen for 19 days. I couldn’t bring myself to tell my friends where I had been – I was the first person in my class to get my period and I was so shy.

One day, a group of young women came to my school to talk to us about menstruation. That was the day everything changed – they taught us so many things and empowered us with knowledge to challenge the traditions. At first my family was angry, and I had to make them understand that we have this tradition because menstruation used to be much more difficult to manage. Now we have pads and it’s much cleaner. It was a difficult process, but there are no longer any restrictions surrounding menstruation in my family.

I am part of Amnesty International’s Student Group at Kathmandu University, and I am changing the way people think about menstruation in the broader sense. We’re making videos, hosting rallies and running community programmes in rural areas for boys and girls. When we hear kids talking about these issues openly, it’s a proud moment for us.

In Nepal, we need to start changing mindsets around the superstitions surrounding menstruation – and I think we’re doing a great job so far.

Poulomi Basu, 36, India

Transmedia artist and activist

I grew up in a patriarchal Hindu household in India, so I am familiar with the use of ritual and tradition as a mechanism to control women. When I started menstruating I wasn’t allowed to enter the kitchen during my period nor could I participate in any festivities. It was only by leaving home that I could be free from patriarchal control and irrational practices and traditions. This is not an option for many women growing up in similar circumstances.

I met Tula, 16, from Nepal, who is barred from household chores during her period, and spends this time working as a porter to contribute to the family’s income. She carries everything from firewood to heavy satellite dishes long distances across rugged terrain so richer families can watch TV. A trip can take her three days and she makes the equivalent of 20 US cents for her efforts. She does this all while studying for her school exams.

Lakshmi, a single mother of three young children in Nepal, is forced into exile by her mother-in-law when she menstruates. Her five-year-old son Roshan is too young to be without his mother and endures the exile alongside her. Despite all the obstacles, Lakshmi’s instinct to protect and provide for her children is undefeated. Her story is a testament to her resilience in the face of such violence and stigma.

I’ve even seen women sent to exile, whilst bleeding post child birth, making it very dangerous for women’s maternal health and reproductive health.

I partnered with Water Aid and launched the ‘To be a girl’ campaign to provide reusable sanitary pads to 130,000 girls across Nepal, India and parts of Africa. I also worked with Action Aid and launched the ‘My Body Is Mine’ campaign to get women to speak up and reclaim the narratives over their own bodies. Through powerful art and storytelling, virtual reality films and workshops in communities, we’re bringing agency to women and helping them speak up against violence. Art has the power to change hearts and minds.

Finally, our efforts have played a role in putting pressure on the Nepalese government who finally criminalised chhaupadi in 2018. Though this is a huge positive step, in some communities the ruling has just driven the practice underground. That’s why this work is more important now than ever.

Haafizah Bhamjee, 22, South Africa

Student and Youth Activist

“Period poverty exists, especially at university. You can’t even talk about menstruation, let alone whether you can afford sanitary products, so girls suffer in silence. It’s dehumanizing”.

My friends and I are trying to change this, through our #WorthBleedingFor campaign. Most people think university is a luxury for the rich, but it’s not. Poor people go to university too. Some students sleep in the library, others line up to receive grocery packs, and lack of access to sanitary pads is a real problem. We’re pushing for universities to install sanitary pad dispensers in bathrooms, and we’ve contacted the local government to provide free pads for girls in schools. We’re also encouraging girls to speak about their experiences.

Seeing people take action feels good. The change is gradual, but it’s exciting. A group of girls have even made a video about #WorthBleedingFor showing our campaigning work. Knowing we’re having an impact is amazing.

Women and girls have fought hard for their human rights over the years – to be educated; to access health care, to own property, to vote, and much more. But, around the world, they continue to face violence and discrimination. Learn more about our women’s rights campaign work.