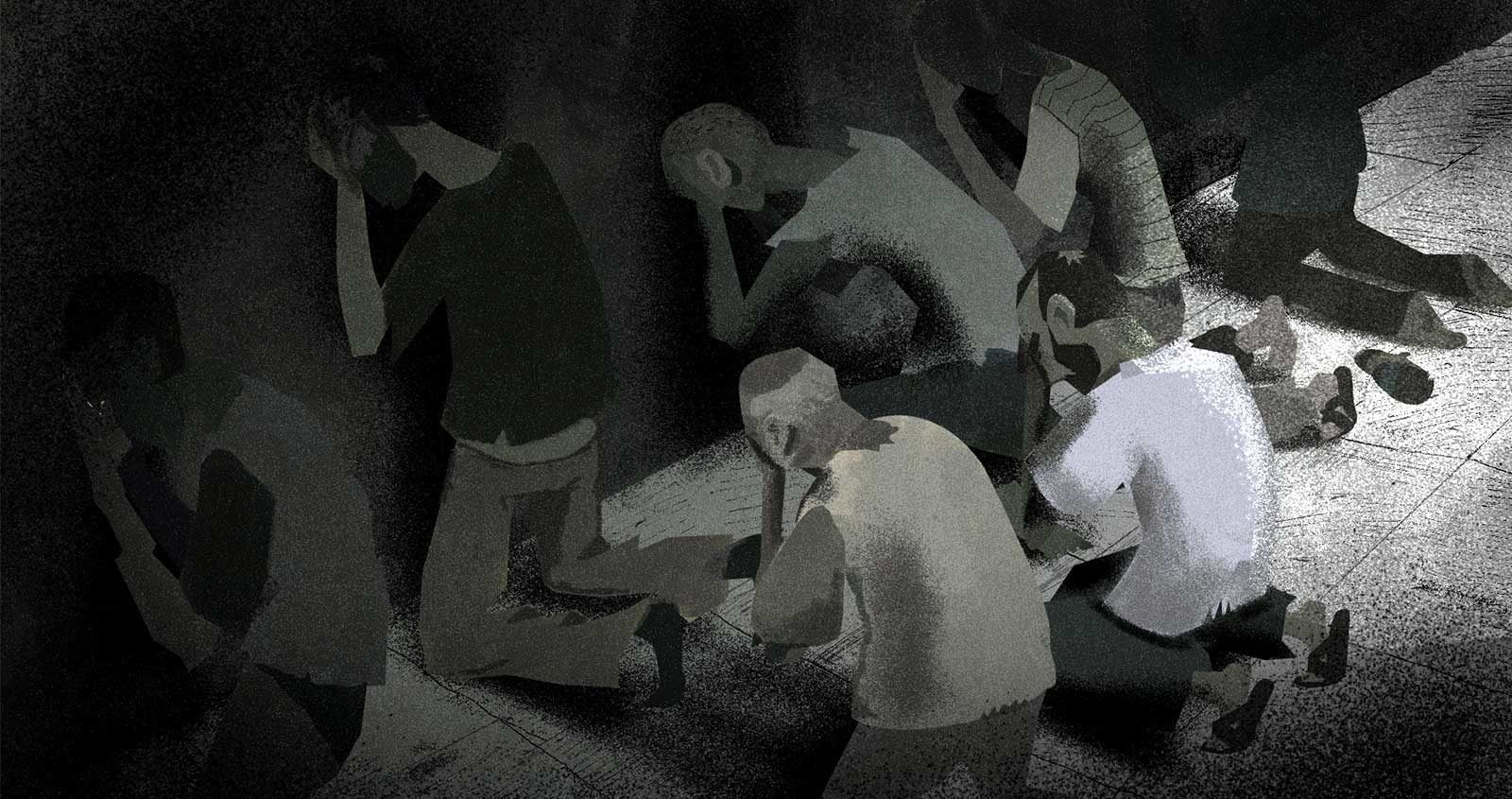

When Amnesty International released a report documenting the mass hanging of thousands of prisoners in Syria’s Saydnaya Prison, the Syrian government was put on the back foot. President Bashar al-Assad himself responded, calling our report “childish” and “fake news”. He even laughed as he said he didn’t know what went on in Saydnaya as he was “in the Presidential Palace”.

The Syrian government is not the first to have its cage rattled by our research.

To coincide with the launch of our 2016/17 Annual Report, let’s look at five tactics for responding to an Amnesty International (AI) report, tried and tested in the past year by human rights violators from around the world:

1 Question our impartiality

Hungarian Government Spokesperson Zoltán Kovács responded to an AI opinion piece about the plight of the Roma in Hungary by accusing us of bias against the government’s immigration policy:

“As a strident critic of this government’s firm stance against illegal immigration, Amnesty International is not interested in a balanced discussion.”

“Amnesty’s principled and impartial approach to human rights research has spoken for itself and continues to be a key agent of change when it comes to protecting the powerless…”

In response to Amnesty’s report documenting the use of chemical weapons in Darfur by the Sudanese government, Sudan’s ambassador to the UK Mohamed Eltom said:

“We don’t think [AI] is a credible organisation”, and accused us of having fabricated other stories about Sudan. Eltom accused us of having an “agenda” – but was unable to explain what it was. Sudan’s envoy to the UN also said that the report was “concocted mainly by a reckless adventurous staffer”.

2 Deny – no need to say why

Some of the authorities implicated in our reports opt for flat-out denial. Asked if treatment of refugees forcibly sent to the remote Pacific island of Nauru amounted to torture, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull replied:

“Well, I reject that claim totally, it is … absolutely false…That allegation, that accusation, is rejected by the government.” He did not elaborate.

In September 2016 we delivered a petition to the government of the Dominican Republic, urging them to end the statelessness crisis facing thousands of people of Haitian descent in the country. President Danilo Medina’s response to journalists was: “I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know what their basis to say that are. They lack information.”

Accusing Amnesty of lying is a good way of slamming the door on the conversation. See the Myanmar Foreign Ministry’s response to a report on Myanmar’s appalling treatment of its Muslim Rohingya minority:

“It is most sad and unfortunate that […] Amnesty International has also based their report on unsubstantiated allegations, made up photos and made up captions”.

3 Whataboutery

One of the oldest tricks in the book. President Assad’s first response to questions about Saydnaya was to deflect attention elsewhere. When the US interviewer suggested that human rights violations might hamper chances for cooperating between the US and Syria, Assad tried to shift the focus to the relationship between the USA and Saudi Arabia: “I will ask you, how could you have this close, very close relation and team relation with Saudi Arabia?”

Assad’s sleight of hand was quickly called out by the interviewer, who pointed out that human rights violations by Saudi Arabia were not the question at hand.

4 Just attack Amnesty

Going a step further than accusing Amnesty International of bias, the Nigerian military chose to respond to our reports that it had shot unarmed Biafran independence protesters with elaborate insults:

“For umpteenth times, the Nigerian Army has informed the public about the heinous intent of this Non-Governmental Organisation which is never relenting in dabbling into our national security in manners that obliterate objectivity, fairness and simple logic.”

“Accusing Amnesty of lying is a good way of slamming the door on the conversation”

Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Maria Zackarova responded to our recent Saydnaya report with wild conjecture about Amnesty’s aims, accusing us of “purposeful provocation, which aims to add fuel to the fire of the subsiding intra-Syrian conflict… and make the Syrians hate each other more.”

Meanwhile Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte called Amnesty International “so naive and so stupid” when we highlighted thousands of extrajudicial killings that have taken place under his administration.

5 Shut us down

If all else fails, outright censorship could do the trick.

In September 2016, Thai officials threatened to arrest Amnesty staff who were preparing to launch a report highlighting the routine use of torture and other ill-treatment by state authorities.

A press conference to mark the launch was canceled after Ministry of Labor officials said the business visas Amnesty staff had did not accord them public speaking privileges, and threatened to charge them should they speak. The attempt to silence us was unsuccessful, only serving to demonstrate the Thai authorities’ contempt for freedom of expression.

For every government who slams our reports with denials, conjecture and conspiracy theories, there are millions of people around the world who speak out in our defense. For more than five decades, Amnesty’s principled and impartial approach to human rights research has spoken for itself and continues to be a key agent of change when it comes to protecting the powerless against some of the worst abuses on the planet.

By Anna Neistat, Amnesty International’s Senior Director for Research.