Billions of dollars of damage, 33 million people affected, one million homes washed away, half a million people in tents, thousands of people including 466 children dead. Some of these include friends and family never to be seen again. These are not figures out of a fiction movie but the unimaginable impact of the recent floods in Pakistan – my homeland.

As a child growing up in Pakistan, monsoon season was happy family time spent eating samosas and drinking tea. There was splashing in the rain and playing in the water. The monsoon has been romanticised in novels and songs. It was the much-needed water for the winter crops – essential to sustaining life at home.

It was never a catastrophe.

Now crops and livestock have been destroyed and people’s lives and livelihoods lost – my people, my home.

Unprecedented rainfall three times higher than the past 30-year average (Red Cross UK) in August created a mega monsoon season, exacerbated by glacial melting owing to the intense heatwave in March.

In short, climate change has amplified a climate emergency to a climate catastrophe, putting millions of people at risk globally. On a personal front it is happening in my home and it is devastating and frightening.

One in seven people, including friends and family, have been affected by the catastrophic monsoon rains, floods and landslides in Pakistan, putting one-third of the country under water, and the worst is not over. In addition to loss of health facilities, infrastructure, agricultural land and livestock, Pakistan is now facing a looming food and housing crisis ahead of the winter season.

With the breakdown of thousands of kilometres of roads and bridges, the desperation is real. People have faced unimaginable choices: do you choose to save one of your six children or the cow that will feed at least five if not all six. The only things people are holding onto in tents are their dear lives and a few odd necessities.

‘People are in dire need of shelter, food, clean water, toilet facilities and medical support. As the local markets are affected, people are unable to buy essential everyday items (Red Cross UK)’.

Women are particularly adversely affected by the floods. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), there are almost 650,000 pregnant women in the flood-affected areas, with almost 73,000 women expected to have delivered in September alone. More than 1,000 health facilities are either partially or fully damaged in Sindh province, and 198 health facilities are damaged in affected districts in Baluchistan.

There is also a heightened possibility of women and girls being at risk of gender-based violence, according to UNICEF, owing to the breakdown of order and social protection mechanisms during a crisis. Menstrual hygiene must also be a focus in the relief programs, with UNFPA estimating the victims of the floods to include 8.2 million women of reproductive age.

More than a thousand schools have been destroyed, putting hundreds of children out of formal education without a foreseeable return in the near future.

Paying the price of climate change

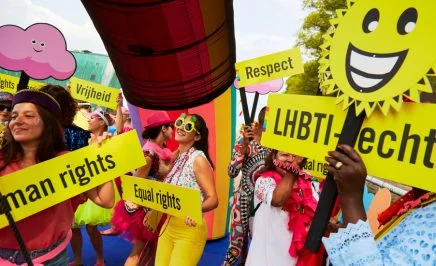

Pakistan presents the perfect case of climate injustice. It is one of the 10 countries in the world most affected by climate change and yet contributes to less than 1% of global carbon emissions. The United States, China and India account for more than half of the world’s carbon emissions and Australia leads other emitters in the Asia-Pacific region. In fact, Pakistan is taking positive action on UN climate goals by embarking on the Ten Billion Tree (plantation) Tsunami Project.

Countries such as Pakistan which are least responsible for climate change are bearing the brunt of its catastrophic impacts. It is a stark reminder that countries most responsible for the climate crisis – mainly the Global North – must provide compensation and remedy for loss and damage that is being borne disproportionately by the Global South or developing countries.

Jeremy Williams’ book ‘Climate Change is racist’ is a provocative but true representation of what is happening. People of colour and from low socio-economic backgrounds are disproportionately harmed by climate change and its effects. Rich white countries like Australia are doing little to nothing about it; some countries even refuse to acknowledge the climate debt they owe to poor countries and marginalized communities.

I agree with Williams. The unfolding and ongoing tragedy in Pakistan is now receiving barely a mention in the media.

Why are developing countries like Pakistan paying such a high price?

Australia has pledged only $5 million to the UN emergency aid appeal of US$160 million for the Pakistan floods, where the estimated damages are US$10 billion.

Although industrialised countries such as Australia agree climate change is happening, there is little to no action from them about paying for the impacts of devastating climate events that are a direct result of the global emissions they have caused. The UN climate negotiators are now referring to climate change and the impact of it as ‘loss and damage’. The 165 countries which are part of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change agree that climate change is here but no one wants to pay for it.

The AUD$145 billion annual climate finance pledge by rich countries to developing countries by the end of 2020 remains unfulfilled. This is unjust and amounts to atmospheric colonisation resulting from deeply entrenched colonial racism.

The COP26 Summit failed to gain agreement between industrialised and developing countries on who pays for the disasters caused by climate change, especially when it is happening in countries that have contributed the least in emissions – how is this fair?

The situation is likely to worsen given Europe’s energy crisis, and the need to explore fossil fuels to fill supply gaps will have a multiplier effect on climate disasters.

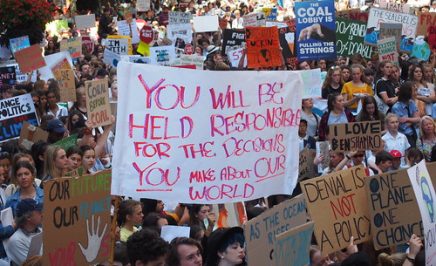

Climate change and the injustice from it is still being argued and tabled at conferences; there is ambition but little action. The world urgently needs climate action, including remedy for loss and damage.

The unprecedented heatwave in Europe and America, including the wildfires and droughts, is a telling sign that rich countries also are not immune from the impact of climate change – what sets them apart from developing countries is their ability to finance, cope and recover from it.

There is hope the November COP27 meeting in Egypt will bring some sensibility and practical steps towards sustainable change on climate.

Our world is collapsing in front of our eyes. The scale and devastation of climate disasters such as what we are witnessing in my homeland of Pakistan must be a wake-up call. We urgently need sustainable climate action and climate finance before displacement from climate disasters reaches unimaginable proportions.

Aima Waheed is Campaign Support Team Coordinator at Amnesty International Australia