Our research reports outline some of the issues in the youth justice system and recommendations for what needs to change at the Federal level and in Western Australia. A similar piece of work in Queensland is currently being put together.

In response to the horrific treatment of children at Don Dale and concerns raised about other youth prisons, Indigenous and human rights advocates are calling for Australia to ratify the Optional Protocol on the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT).

Julian Cleary, Indigenous Rights Campaigner from Amnesty International breaks down what OPCAT actually is and why it is important.

1. What is CAT?

CAT is the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. It’s a human rights treaty that Australia has signed and agreed to be bound by (i.e ratified).

CAT defines torture as any act by a public official that intentionally inflicts severe mental or physical pain or suffering on a person.

CAT requires Australia to take legislative, judicial and other measures to prevent acts of torture in any territory under its jurisdiction. Acts like the Guantanamo-style treatment of children we saw at Don Dale.

There is a Committee against Torture that considers whether Australia is honouring the obligations we have agreed to be bound by under CAT. The meeting of that Committee about Australia was in December 2014.

In November 2014, Amnesty wrote to the Committee against Torture outlining concerns about the tear gassing and treatment of children at Don Dale and raising other concerns about conditions of youth detention for boys and girls in the NT and other states.

In its report on Australia, the CAT Committee said that it had been made aware that “overrepresentation of Indigenous people in prisons has a serious impact on Indigenous young people and Indigenous women”. The Committee recommended that Australia increase its efforts to “address the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in prisons, in particular its underlying causes”.

The Committee also said that Australia should strengthen its efforts to bring the conditions of detention into line with international standards. To achieve this, the CAT Committee recommended that Australia become a party to the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT) as soon as possible.

2. What’s OPCAT?

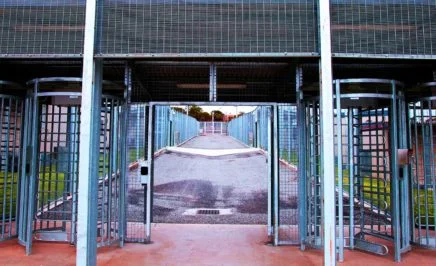

OPCAT is a way for Australia to strengthen its commitment to stamp out torture, and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in youth prisons and other places of detention. OPCAT requires countries that ratify it to set up a system of unannounced and unrestricted visits to all places of detention by independent national and international monitoring bodies.

OPCAT is a way for Australia to strengthen its commitment to stamp out torture, and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in youth prisons and other places of detention.

By ratifying OPCAT Australia would be required to set up an independent body or bodies with financial independence and the power to access all places of detention in all states and territories (the National Preventative Mechanism/s). It would also permit the UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture to visit any place of detention in Australia.

In November 2015, Australia’s human rights record was reviewed by other countries at the United Nations. In recognition that our current systems are not up to scratch, 27 countries said Australia should get on with ratifying OPCAT. These recommendations were made due to concerns about conditions in youth detention centres, prisons and immigration detention in Australia.

In November 2014, Amnesty wrote to the Committee against Torture outlining concerns about the tear gassing and treatment of children at Don Dale.

In response to concerns raised by a number of countries and NGOs about conditions of youth detention, the Australian Government claimed that:

“Juvenile justice centres in Australia provide secure and safe care of young people who are sentenced to custody or who are remanded pending the finalisation of their court matter”.

The Australian government has said that it is “actively considering” the ratification of OPCAT, but has failed to do so.

3. Why is ratifying different to signing and why is it important?

Signing a human rights treaty demonstrates a broad intention to comply with it, but this is not binding. Australia signed OPCAT back in 2009, but has failed to ratify it for seven years.

By ratifying OPCAT the Australian Government would be required to consult nationally and work with the states and territories to set up an OPCAT compliant National Preventative Mechanism (or Mechanisms) within a year.

4. What would this mean for kids in detention?

Ratifying OPCAT would ensure that youth detention centres and police lock-ups are subject to much stronger independent oversight and monitoring to stop abuse of children in the justice system throughout Australia.

As well as conducting visits to these facilities, the National Preventative Mechanism would be able to

- conduct confidential interviews with children in detention;

- review and comment on laws and policies (like restraint chairs and spit hooding)

- make recommendations to improve the treatment and conditions of children in detention; and,

- maintain contact with the UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture.

At the moment, no agency in any Australian state or territory monitors youth detention facilities and police lock-ups in a way that fully complies with OPCAT. Surprisingly, given its shocking record on locking up Indigenous children, Western Australia probably has the strongest system of independent oversight in place.

After some disturbing incidents in 2013, including extended lock-down of children in detention and the transfer of children to the adult prison, inspections and reports by the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services (OICS) have led to big improvements in youth detention conditions in Western Australia (though the OICS notes that there is still some way to go).

Importantly though, the OICS does not have the power to access police stations or lock-ups, which is a major gap. This would need to change under OPCAT.

5. Should kids even be in detention in the first place?

The short answer is no. Only as a last resort and all other alternatives need to be considered and tried first. But this is not the reality right now, especially for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Like countless reports before it, Amnesty’s research highlights how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are more likely to be charged rather than cautioned, more likely to be arrested than summonsed, more likely to be refused bail and held in custody awaiting trial and more likely to be sentenced to detention.