Israeli authorities must end their indefinite incommunicado detention of Palestinians from the occupied Gaza Strip, without charge or trial under the Unlawful Combatants law, in flagrant violation of international law, said Amnesty International.

- Abusive Israeli law used to arbitrarily detain Palestinians from Gaza indefinitely without charge or trial

- Unlawful Combatants Law legalizes incommunicado detention, enables enforced disappearance and must be repealed

- Harrowing torture testimony from 27 former detainees, including a 14-year-old boy

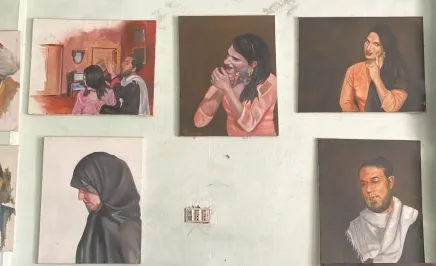

The organization documented the cases of 27 Palestinian former detainees, including five women, 21 men and a 14-year-old boy, who were detained for periods of up to four and a half months without access to their lawyers or any contact with their families, in connection with this law. All those interviewed by Amnesty International said that during their incommunicado detention, which in some cases amounted to enforced disappearance, Israeli military, intelligence and police forces subjected them to torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

The Unlawful Combatants Law grants the Israeli military sweeping powers to detain anyone from Gaza that they suspect of engagement in hostilities against Israel or posing a threat to state security for indefinitely renewable periods without having to produce evidence to substantiate the claims.

“While international humanitarian law allows for the detention of individuals on imperative security grounds in situations of occupation, there must be safeguards to prevent indefinite or arbitrary detention and torture and other ill-treatment. This law blatantly fails to provide these safeguards. It enables rampant torture and, in some circumstances, institutionalizes enforced disappearance,” said Agnès Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International.

“Our documentation illustrates how the Israeli authorities are using the Unlawful Combatants Law to arbitrarily round up Palestinian civilians from Gaza and toss them into a virtual black hole for prolonged periods without producing any evidence that they pose a security threat and without minimum due process. Israeli authorities must immediately repeal this law and release those arbitrarily detained under it.”

Agnès Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International

Amnesty International is calling for all detainees held under the Unlawful Combatants Law, including suspected members of armed groups, to be treated humanely and given access to lawyers and international monitoring bodies such as the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC). Those suspected of responsibility for crimes under international law must be tried in line with international fair trial standards, while all civilians detained arbitrarily without charge or trial must be immediately released.

The Israeli Prison Service (IPS) confirmed to the Israeli NGO Hamoked that as of 1 July 2024, 1,402 Palestinians were detained under the Unlawful Combatants law. This number excludes those held for an initial 45-day period without formal order.

Between February and June 2024, Amnesty International documented 31 cases of incommunicado detention and found credible evidence of widespread use of torture and other ill treatment. Interviews were conducted with 27 released detainees – all civilians arrested from the occupied Gaza Strip (21 men, five women and one child). The organization also interviewed four family members of civilians detained for up to seven months whose whereabouts are yet to be disclosed by Israeli authorities and two lawyers who recently managed to meet with detainees.

Israeli military seized the detainees from locations across Gaza including Gaza City, Jabalia, Beit Lahiya and Khan Younis. The detainees were rounded up at schools housing internally displaced people, during raids on homes, hospitals, and newly installed checkpoints. They were then transferred to Israel and held for periods ranging from two weeks to up to 140 days in military or IPS-run detention facilities.

Those detained included doctors taken into custody at hospitals for refusing to abandon their patients; mothers separated from their infants while trying to cross the so-called “safe corridor” from northern Gaza to the south; human rights defenders, UN workers, journalists and other civilians.

All those interviewed by Amnesty International said they were subjected to torture and other ill-treatment.

“Torture and other ill-treatment including sexual violence are war crimes. These allegations must be independently investigated by the International Criminal Court’s prosecutor’s office. This is crucial due to the documented failure of the Israeli judiciary to credibly investigate torture allegations by Palestinians in the past. Israeli authorities must also grant immediate and unrestricted access to all places of detention to independent monitors – access that has been denied since 7 October,” said Agnès Callamard.

Detention of Palestinians from Gaza under the law

The Detention of Unlawful Combatants Law, enacted in 2002, was invoked for the first time in five years following the horrific attacks perpetrated by Hamas and other armed groups on 7 October in southern Israel.

The Israeli military initially invoked the law to hold alleged participants in the 7 October attacks, but shortly thereafter expanded its use to detain Palestinians from Gaza en masse without charge or trial. The lack of due process means that both civilians and those directly engaging in hostilities have been detained under this law.

For the first 45 days of detention, the military are not required to issue a detention order. The law denies detainees access to a lawyer for up to 90 days, codifying incommunicado detention, which in turn enables torture and other ill treatment.

Detainees must be brought before a judge within a maximum period of75 days of their detention for judicial review, but judges typically rubberstamp the detention order in sham proceedings.

The law does not stipulate a maximum time for detention and allows security services to hold detainees under indefinitely renewable orders.

Amended law facilitates incommunicado detention

The Unlawful Combatants Law was originally enacted in 2002 to allow for the prolonged detention without charges or trial of two Lebanese nationals, who were not under Israeli jurisdiction. Since its unilateral “disengagement” from the occupied Gaza Strip in 2005, Israel has used this law to hold people from Gaza it deems a national security threat for indefinitely renewable periods.

In December 2023, the Israeli authorities passed a temporary amendment to the law, extending the time the military is permitted to detain Palestinians without a detention order from an initial 96 hours (extendable up to seven days) to up to 45 days. It also increased the maximum time a detainee can be held before being brought before a judge to review the detention order from 14 days to 75 days and extended the period a detainee can be held without seeing a lawyer from 21 days to up to six months, later reduced to three months. This amendment was renewed again in April 2024.

Evidence justifying the detention is withheld both from the detainee and their lawyer. This means many of those detained are held for months without the slightest idea of why they have been detained, in violation of international law, completely cut off from their family and loved ones and unable to challenge the grounds of their detention.

Two detainees told Amnesty International they were brought before a judge twice for virtual hearings and on both occasions were unable to speak or ask questions. Instead, they were simply informed that their detention had been renewed for a further 45 days. They were never informed of the legal basis of their arrests nor of what evidence had been brought against them to justify their arrests.

Following a petition brought before the Israeli Supreme Court by Hamoked on behalf of a detained X-ray technician from Khan Younis, the state informed the Court in May 2024 that lawyers can apply to visit detainees from Gaza 90 days after their detention. Only a very limited number of such applications has been approved since.

In addition to being denied access to legal counsel, detainees are also cut off from their families. Families described to Amnesty International the agony of being separated from their loved ones and living in constant fear of discovering that they died in prison.

Alaa Muhanna, whose husband Ahmad Muhhana, the director of Al-Awda hospital, was detained during a raid on the hospital on 17 December 2023, told Amnesty International the only scant information she receives about him is from other released prisoners: “I assure the children that Ahmad is fine, that he’s coming back soon, but to live through this war, the constant displacement, the bombing and also have to fight to know where your husband is, not to hear his voice, is like a war within the war.”

One released health worker told Amnesty International that not knowing whether his family in Gaza were alive or dead while he was detained was “even worse than torture and starvation”.

Torture and other ill-treatment

The extensive periods of incommunicado detention facilitate torture by eliminating any monitoring of the physical condition of detainees and communication with them.

The 27 released detainees, interviewed by Amnesty International, consistently described being subjected to torture on at least one occasion during their arrest. The organization observed marks and bruises consistent with torture on at least eight detainees interviewed in person and also reviewed medical reports of two detainees corroborating their accounts of torture.

Amnesty International’s Crisis Evidence Lab verified and geolocated at least five videos of mass arrests including of detainees filmed while stripped to their underwear after being detained from northern Gaza and in Khan Younis. Public forced nudity for long durations violates the prohibition of torture and other ill-treatment and amounts to sexual violence.

Those held at the notorious Sde Teiman military detention camp, near Beersheba in southern Israel said they were blindfolded and handcuffed for the entire time they were detained there. They described being forced to remain in stress positions for long hours and being prevented from talking to one another or raising their heads. These accounts are consistent with findings of other human rights organizations and UN bodies as well as numerous reports, based on accounts of whistleblowers and released detainees.

One detainee who was released in June after 27 days during which he was detained in a barrack with at least 120 others told Amnesty detainees they would be beaten by the military or sent to be attacked by dogs simply for talking to another prisoner, raising their head or changing position.

Said Maarouf, a 57-year-old pediatrician who was detained by the Israeli military during a raid on al-Ahli Baptist hospital in Gaza City in December 2023 and detained for 45 days at the Sde Teiman military camp, told Amnesty International that detention guards kept him blindfolded and handcuffed for the entire duration of his detention, and described being starved, repeatedly beaten, and forced to sit on his knees for long periods.

In another case, the Israeli army arrested a 14-year old child from his home in Jabalia, in northern Gaza on 1 January 2024. He was held for 24 days in the Sde Teiman military detention centre with at least 100 adult detainees in one barrack. He told Amnesty International that military interrogators had subjected him to torture, including by kicking him, punching him in the neck and head. He said he had been repeatedly burnt with cigarette butts. Signs of cigarettes burns and bruises were visible on the child’s body when Amnesty International interviewed him on 3 February 2024, in the school where he was sheltering with other displaced families. During his detention, he was not allowed to call his family or see a lawyer and was held blindfolded and handcuffed.

On 5 June Israeli authorities announced plans to improve detention conditions at Sde Teiman military camp and limit the number of detainees held at the site in response to a petition from Israeli human rights organizations demanding its closure, but over a month later little appears to have changed.

The lawyer Khaled Mahajna was able to gain rare entry into Sde Teiman on 19 June. He told Amnesty International that his client, Mohammed Arab, a detained journalist, told him he was being held with at least 100 people in the same barrack in inhumane conditions and that the detainees had seen no improvement whatsoever over the past two weeks. He also said he had been held in Sde Teiman for over 100 days, without even knowing why.

The Israeli military confirmed to Haaretz on 3 June that it is investigating the deaths in custody in Israel of 40 detainees, including 36 who died or were killed in the military detention facility in Sde Teiman. No indictments have been filed yet. This number does not include detainees who died or were killed while in the custody of the Israeli Prison Service.

Women detainees

Among the detainees interviewed by Amnesty International were five women all of whom had been detained incommunicado for over 50 days. They were first held in a women-only detention camp at Anatot military detention centre, in an illegal Israeli settlement near Jerusalem in the occupied West Bank, then in Damon prison for women in northern Israel, under the control of the Israeli Prison Service. None of the five was informed of the legal grounds for their arrest or brought before a judge. All of them described being beaten while being transported to detention.

One of them, arrested on 6 December from her home, said she was separated from her two children- a four-year-old and a nine-month-old baby – and held initially alongside hundreds of men. She was accused of being a Hamas member, beaten, forced to remove her veil and photographed without it. She also described the torment of being subjected to the mock execution of her husband:

“On the third day of detention, they put us in a ditch and started throwing sand. A soldier fired two shots in the air and said they executed my husband and I broke down and begged him to kill me too, to relieve me from the nightmare,” she said.

“I was terrified and scared for my kids all the time,” another released woman detainee told Amnesty that her repeated requests for information about her children were ignored by prison guards whom she overheard laughing and mocking her.

She told Amnesty International that after three weeks at Damon prison she was told she would be released. She was handcuffed, blindfolded and had her feet shackled and was taken to another location. Upon arrival there, instead of being released she was violently strip-searched by guards who used a huge knife to rip off her clothes. She was then returned to Anatot for 18 more days.

She told Amnesty that she was threatened by prison guards who said: “We will do to you what Hamas did to us, we will kidnap and rape you”. She was never informed of the reason for her detention.

She and other detainees interviewed by Amnesty International said that they were dropped off near Kerem Shalom/Karem Abu Salem crossing and had to walk for more than half an hour until they reached an ICRC -run point for released prisoners. All detainees said that all or most of their belongings were never returned to them, including their phones, jewellery and money.

Background

Amnesty International expressed grave concerns over Israel’s use of the Unlawful Combatants Law and its violations of international human rights law in a 2012 report Starved of Justice: Palestinians detained without trial by Israel. As explained in detail in that report, Israel previously derogated from its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) citing the fact that the nation has been in a declared state of emergency since its formation, a derogation that continues to this day. However international humanitarian law, which is not subject to derogation, requires that the right to a fair trial must always be respected. In addition, Article 4(2) of the ICCPR prohibits derogation from certain rights in the ICCPR even during a state of emergency, including the right not to be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 7).

Accordingly, incommunicado detention, the lack of fair trial, and torture and other ill-treatment violate international law, even during a state of emergency.

Beyond this law, Israeli authorities have a history of incarcerating Palestinians without charge or trial through their systematic use of administrative detention, a key feature of Israel’s system of apartheid. According to Israeli human rights organization Hamoked, as of 1 July Israeli authorities were holding 3,379 people under administrative detention, the vast majority of whom are Palestinians from the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem.