Salar Shadizadi, who was sentenced to death for a crime he committed when a child, was released after 10 years from Rasht prison in northern Iran.

Salar, now 25, had faced imminent execution several times in connection with a murder that took place when he was just 15 years old.

In a letter from prison in 2015, Salar explained that he “unintentionally” caused the “catastrophic” death of his childhood friend by stabbing a moving object under a cloth during a “silly game” in the dark. His friend had dared him to go into the garden at night, knowing that Salar was very afraid. Salar said he had only realised it was his friend after he had stabbed the object.

Salar had said that he was tortured and otherwise ill-treated in the investigation stage of his case and was not granted access to a lawyer until his case was sent to court for trial. In December 2007, he was sentenced to death, a sentence which the Supreme Court later upheld. He was granted a retrial in early 2016 after a global outcry but was re-sentenced to by hung in November 2016.

In February 2017, the family of the deceased agreed to grant him a pardon in exchange for “blood money” (diyah) and he was released on 25 April 2017. According to Iranian law, those sentenced to ‘Qesas’ (retribution), can only be spared the death penalty if the family of the victim agrees to accept a payment.

How did Amnesty respond?

In In January 2016, the Australian section of Amnesty created an online petition for the then-49 people sentenced to death in Iran for crimes committed when they were children, including Salar. Over 12,000 people signed the petition, which was then sent to the Iranian authorities.

Urgent actions were issued to the global movement and thanks to intense advocacy and campaigning efforts spearheaded by Amnesty, all his scheduled executions were halted – often at the last minute.

The issue in depth

At least 78 juvenile offenders remained on death row in 2016 and least two juvenile offenders were executed in Iran in 2016. Amnesty International received reports that five other juvenile offenders were among those executed, but was unable to verify the age of those individuals at the time of the crime.

Scores of people who were below 18 years of age when the crime was committed were granted retrials, based on the juvenile sentencing provisions in the 2013 Islamic Penal Code, but were sentenced to death again after the courts concluded that they had attained sufficient “mental maturity” at the time of the crime. Among these people were Salar Shadizadi, as well as Himan Uraminejad, Hamid Ahmadi, Sajad Sanjari, Alireza Tajiki and Amanj Veisee.

Overall, Iran carried out at least 567 executions in 2016, including at least eight women. However the authorities only announced 242 of those executions through official and semi-official sources. At least 33 executions were carried out in public.

What’s next?

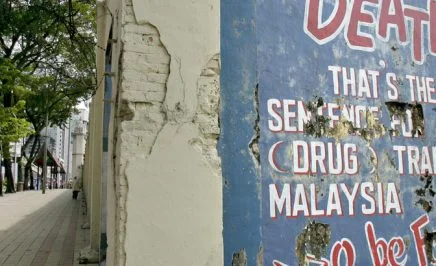

International human rights treaties prohibit courts sentencing to death or executing anyone who was under the age of 18 at the time the crime was committed. But a small number of countries, including Iran, continue to sentence child offenders to death.

Amnesty International will continue to campaign for the abolition of the death penalty globally in the handful of countries still sentencing children and adults alike to execution. In an unprecedented step, one country is trying to reinstate the death penalty – The Philippines. We need to take action, before this happens.