On 10 October, as people around the world mark the World Day Against the Death Penalty, we reiterate our position that there is no convincing evidence that the death penalty has a unique deterrent effect on crime, including for drug-related crimes.

This is a join position shared with ELSAM (Institute for Policy Research and Advocacy), HRWG (Human Rights Working Group), ICJR (Institute for Criminal Justice Reform), Imparsial, LBH Masyarakat (Community Legal Aid Institute) and PKNI (Indonesian Drug User Network) .

The death penalty violates the right to life, as recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment.

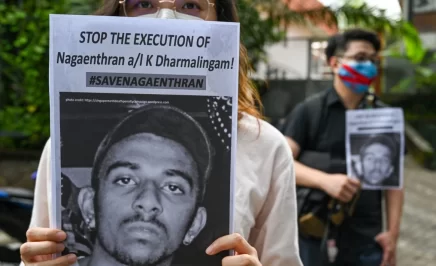

Our organizations are deeply concerned that – despite the fact that research findings made by NGOs and the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) have pointed to systemic flaws in the administration of justice in Indonesia and violations of the right to a fair trial and other international safeguards that must be observed in all death penalty cases – the Indonesian government still carried out executions of four men on 29 July 2016 for drug-related offenses.

Three of the prisoners had appeals pending when they were executed. On the same day the Indonesian authorities also gave a last minute stay of execution for 10 other prisoners to allow them to review their cases after facing a national and international outcry.

We are also concerned that many others currently facing execution may not have had legal assistance to enable them to file appeals for further judicial reviews. We urge the authorities to extend the review of death penalty cases to all those currently under sentence of death. International law sets out key safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty that must be observed in all cases.

These include the right to a fair trial; the right not to be subjected to torture or to other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; and the right to apply for clemency or pardon of a death sentence. Further, drug-related offences do not meet the threshold of the “most serious crimes” to which the use of the death penalty must be restricted under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a treaty Indonesia acceded to in 2006.

The continued use of the death penalty in Indonesia may also undermine efforts by the Indonesian government to protect its citizens from being subjected to judicial execution in other countries. Our organizations oppose the death penalty unconditionally, in all cases without exception, regardless of the nature or circumstances of the crime, the guilt, innocence or other characteristics of the individual, or the method used by the state to carry out the execution.

As of today…

140 countries are abolitionist in law or practice. Four more countries – Fiji, Madagascar, Republic of Congo and Suriname- became abolitionist for all crimes in 2015 alone and the Parliament of Mongolia adopted a new Criminal Code at the end of last year, effective from 2017, removing the death penalty as a possible form of punishment under the laws of the country. Nauru became the 103rd abolitionist country this year. The continued use of the death penalty in Indonesia has not only set the country against its international obligations, but also against the global trend towards abolition of this ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment.

Our organizations renew our calls on the government of Indonesia to establish a moratorium on executions as a first step towards abolition of the death penalty. We also call on the authorities to ensure that, pending full abolition, they immediately establish an independent and impartial body, or mandate an existing one, to review all death penalty cases, with a view to commuting the death sentences or to offer a retrial that fully complies with international fair trial standards and which does not resort to the death penalty.

Background

The death penalty has been a part of Indonesia’s legal system since before the country’s independence in 1945, and can be imposed for a broad range of crimes. However it is usually imposed for murder with deliberate intent and premeditation; drug-related crimes (producing, processing, extracting, converting or making available narcotics); and terrorism-related offences.

There have been 18 executions – which all for drug trafficking offences – carried out under the administration of President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo, who took office in October 2014. Under Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who was President of Indonesia from 2004 to 2014, there were 21 executions.

In December 2014, when newly-appointed, President Widodo publicly stated that he would not grant clemency to any individuals who had been sentenced to death for drug-related crimes, undermining their right to seek pardon or commutation of their death sentence. To date, at least 175 people remain under sentence of death in Indonesia for murder, drug-related crimes and terrorism-related crimes.

A new draft Criminal Code was submitted to lawmakers by the government in March 2015. It includes provisions that would allow for a death sentence to be commuted to life imprisonment (set at 20 years) in certain, limited, circumstances. Furthermore, if the request for clemency is denied and the death penalty is not carried out after 10 years, the President can commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. The draft law is currently being deliberated in the House of Representatives.