Australia is facing a severe housing crisis. Pensioners are living in their cars; single parents and their children are couch surfing. Across Australia people want to see solutions to the housing crisis, so everyone has a place to call home. A recent survey revealed that housing was young people’s top priority this election.

And as the election ramps up, parties are releasing their housing policies but, so far, those policies fail to protect housing as a human right. Research shows that countries that protect people’s human right to housing reduce homelessness. That’s why we’re calling on the next Australian Government and Parliament to protect housing as a human right in a Human Rights Act.

A Human Rights Act that protects the right to housing – and gives people a tool to challenge human rights abuses – will help ensure everyone in Australia has somewhere safe and secure to sleep.

The current state of the Australian housing crisis

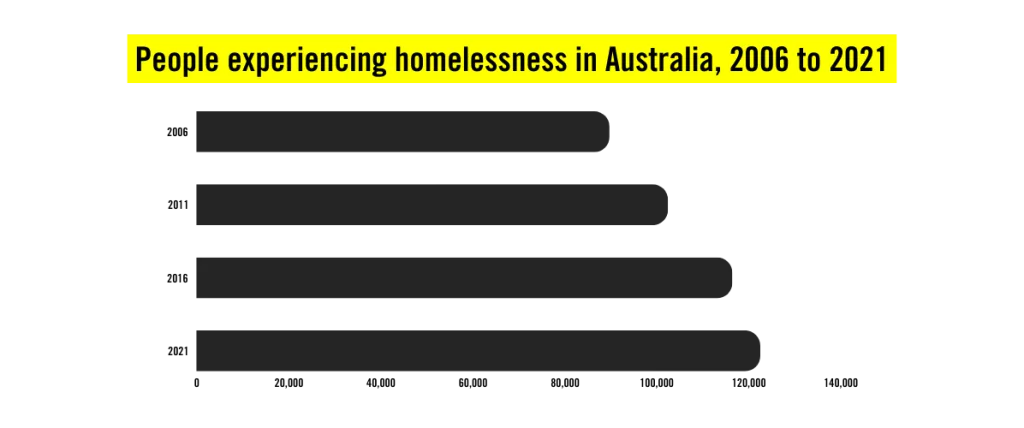

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the number of people classified as homeless has been increasing steadily since 2006.

In 2024, Anglicare conducted a ‘Rental Affordability Snapshot’ by surveying all the rental properties listed across Australia. Out of 45,115 rental listings:

- 31 were affordable for a person on the Disability Support Pension.

- 3 were affordable for a person on JobSeeker.

- 0 were affordable for a person on Youth Allowance.

With Australian wages no longer keeping up with the cost of living, accessing stable housing is increasingly now a luxury not everyone can afford.

There are several causes of the housing crisis in Australia including:

- Housing is a commodity. Housing has increasingly been treated as a means to make money, rather than as a basic human right. This has led to speculative investments and inflated property prices.

- Australian wages have not kept pace with the rising cost of living. This disparity has pushed many into rental markets, driving up rental prices and reducing the availability of affordable housing.

- Lack of legal protections – Without a federal law that guarantees everyone’s right to adequate housing, Australians face an increasing lack of secure, stable and accessible housing. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data shows there has been a decline in the proportion of social housing households, dropping from 4.7% of all households in 2013 to 4.1% in 2023.

Without a Human Rights Act, government policies are not obligated to respect human rights. It’s the reason why today’s Australian housing policies aren’t focused on the fact that housing is a human right. Instead, they’re designed to promote investment.

With a Human Rights Act, people suffering rights abuses like homelessness could challenge injustices. It would give everyone a tool to challenge and remedy those abuses, creating a fairer future.

We know that human rights-based housing policies make a difference.

In 2008, Finland introduced a human-rights based policy aimed at ending homelessness. It focussed on placing community members in stable, long-term accommodation, rather than short-term accommodation. Today, there are almost no rough sleepers in Finland.

Over 50 jurisdictions around the world have protected the right to housing. In February 2025 the Human Rights Law Centre and the UTS Faculty of Law have released a report highlighting how these protections have improved people’s lives, and the difference a Human Rights Act would make to people in Australia.

In Australia, Queensland, Victoria, and the Australian Capital Territory have Human Rights Acts but none of them explicitly protect the right to adequate housing. State Housing Acts also regulate the management of social housing, however there is no specific legal right to housing in any Australian laws or the Constitution.

People have used state human rights acts to secure their right to housing before.

In Queensland, a single mother who had experienced domestic violence successfully challenged her eviction using the Queensland Human Rights Act. The woman’s former partner had damaged their rental, leading to an eviction notice. With the help of Tenants Queensland, she was able to transfer the tenancy into her name, securing the home for herself and her children.

Australia does provide various forms of housing assistance and support programs to help people access affordable housing. These include things like public housing and rental assistance. But the programs on offer don’t come close to meeting the need. And in spite of these programs, too many people are still suffering from homelessness. In these cases, the state is failing in its obligation under international law to protect our right to adequate housing.

The right to housing under international law

The right to housing is enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), a treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1966. Article 11 imposes obligations on state parties to take steps to realise the right to adequate housing.

‘Adequate housing’ means more than just a right to shelter. It’s the right to access decent housing, which is defined by several factors:

- Legal security of tenure

- Availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure,

- Affordability and accessibility

- Habitability

- Location and cultural adequacy.

As a party to this treaty, Australia has an obligation to ensure the affordability and accessibility of housing, including focusing on protecting the human rights of our most vulnerable.

What’s next?

We’re closer than ever to protecting all our human rights in law. A Labor-led Parliamentary Committee recently recommended the government legislate a Human Rights Act.

Amnesty is calling on the next Australian Government and Parliament to accept that recommendation and legislate a Human Rights Act to protect all our human rights – including our right to housing.

To get them to commit to legislating an Act, we need to show the next Australian government and Parliament that people support a Human Rights Act and want them to legislate one.

Australia has a choice

Elections are a critical opportunity to shape our nation’s future. What kind of country do we want Australia to be? Who should represent us? What values should guide our leaders?

As Australians go to the polls next month, we have the opportunity to put human rights on the political agenda.

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all – and we can only do it with your support.

Act now or learn more about our human rights work.