Uyghurs overseas often hesitate to publicly talk about human rights abuses against them and their relatives due to fear of repercussions for their relatives back in China. In spite of such challenges, six parents have decided to publicly share their stories in the hope that it will help them reunite with their children soon.

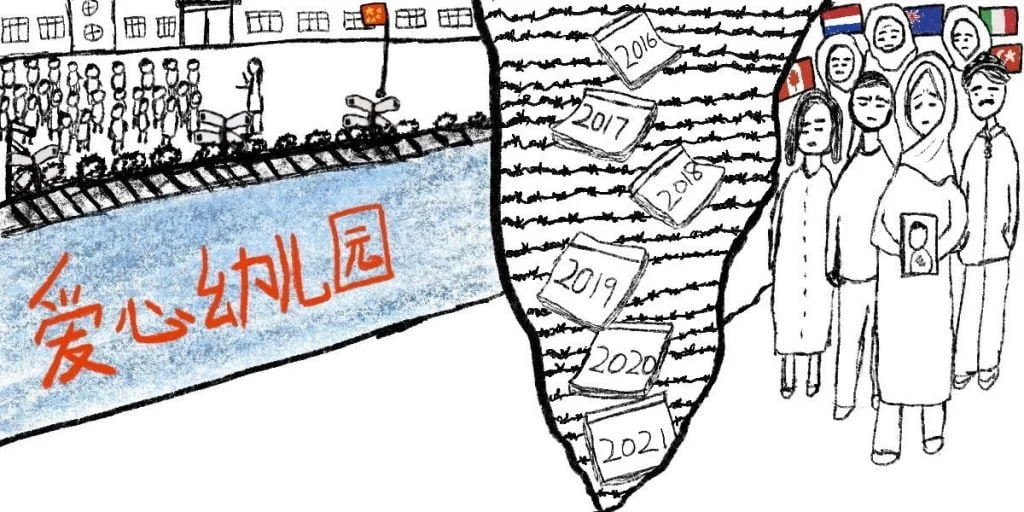

The exiled families of Uyghur children held in state “orphanages” in the Chinese region of Xinjiang described the torment of being separated in a new piece of Amnesty International research released today.

For decades, many Uyghurs have experienced systematic ethnic and religious discrimination in northwestern China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) as part of China’s publicly declared “People’s War on Terror” and its associated efforts to combat “religious extremism”.

Since 2014, an estimated one million or more people have been a part of a mass detention campaign in Xinjiang, where they have been subjected to various forms of torture and ill-treatment, including political indoctrination and forced cultural assimilation.

Nearly four years ago, Uyghur parents studying or making a living abroad began living a recurring nightmare. Many had left one or more children in the care of family members in their hometowns back in Xinjiang. They could not know at the time that China was about to launch an unprecedented crackdown on ethnic populations in the region that would make it nearly impossible for their children to leave China to reunite with them abroad.

Amnesty International has spoken extensively to six parents who have been separated from their children. Their testimonies only begin to scratch the surface of the experiences of Uyghur families yearning for reunification with children trapped in China. These are two of the stories.

“THERE ARE CADRES AT HOME” – Mamutjan’s story

Mamutjan, born and raised in Kashgar, currently lives in Australia. He was pursuing a doctoral degree in social science in Malaysia when his wife Muherrem and baby daughter joined him in 2012, after waiting more than two years for Muherrem’s passport to be issued.

Mamutjan still cherishes the time they were all together: “When Muherrem and our daughter first came to Kuala Lumpur, it was so exciting … Those were the happiest and most memorable times of my life.”

Those happy times lasted almost three years, ending when the Chinese embassy in Kuala Lumpur refused to reissue Muherrem’s passport in late 2015, after it had been lost. She was then forced to travel back to China to renew her passport with their then five-year-old daughter and six-month-old son. At the time, they thought this would be a routine procedure. They had no inkling that China was about to launch a large-scale crackdown on Uyghurs and that an agonizing, years-long separation was about to begin.

For two years, Mamutjan knew little about his wife’s whereabouts and was unable to contact his parents or in-laws. In May 2019, Mamutjan saw a video of his son on a relative’s social media account, excitedly shouting: “My mum has graduated!” He then finally found some peace of mind, as he believed this clearly meant she had been released from the camps.

Muherrem and the two children ended up stranded in Kashgar. Mamutjan was able to maintain regular contact up until the day before Muherrem was taken to an internment camp in April 2017. When Muherrem was taken away, the children were left with their grandparents. Not long after, Mamutjan’s parents asked him not to contact them again. Many of his friends and relatives have “unfriended” him on messaging apps.

Mamutjan decided to take a chance and called his parents in August 2019. He thought the video might be a sign that his family’s dire situation had improved somewhat.

He was so excited when his mother picked up the phone. “I just wanted to say Eid Mubarak, it’s been so long since the last time I spoke to you,” Mamutjan said.

His mother replied with a quavering voice before she hung up: “There are cadres at home.”

“We did not deserve any of this immense suffering. It’s like you lose four or five years of your life just for being Uyghur or being different from the majority of Chinese”

– Mamutjan

Afterwards, Mamutjan kept calling but the line was always busy. He believes his parents deliberately disconnected the line so that he could not call again, avoiding contact with him for fear that being in touch with people overseas could lead to internment or other punishment.

Over the last year, Mamutjan has continued to receive bits of information in coded words from his friends that suggest Muherrem continues to be detained. A friend told him that his wife was “five years old”, which Mamutjan believes might mean that she was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. Another friend said Muherrem has been taken to a “hospital”, which could refer to an internment camp or a prison in the coded language Uyghurs use.

While Mamutjan has not been able to contact his family and relatives, he believes his son might be living with his mother-in-law and his daughter with his own parents, based on two videos he received from close friends who visited his hometown to find out more information about his family. “We did not deserve any of this immense suffering. It’s like you lose four or five years of your life just for being Uyghur or being different from the majority of Chinese,” he said.

Mamutjan called on the Chinese government to end its repressive policies in Xinjiang: “If there is any humanity left in them, the Chinese authorities should stop treating people like this and let people reunite with their families. It is not like we have committed any crimes. I want them to realize the extent of this mass cruelty … This is agonizing and painful injustice, there are no other words to accurately describe this.”

He has reached out to the Department of Home Affairs in Australia, where he is currently living, but they said they could not help him because he is not a permanent resident.

“ALMOST REUNITED: FOUR TEENAGERS ON A PERILOUS JOURNEY” – Mihriban Kader‘s story

Mihriban Kader and her husband Ablikim Memtinin, originally from Kashgar, fled to exile in Italy in 2016 after being repeatedly harassed by police and told to hand over their passports to the local police station.

Soon after they left, the police also started to harass Mihriban’s parents, who were taking care of their four children. Eventually, the grandmother was taken to a camp and the grandfather was interrogated for several days and later spent months in hospital.

This left the children without any caretaker. “Our other relatives didn’t dare to look after my children after what had happened to my parents,” Mihriban told Amnesty International. “They were afraid that they would be sent to camps, too.”

Fresh hopes for a family reunion came in November 2019, when Mihriban and Ablikim received a permit from the Italian government to bring their children to join them. Before that could happen, however, their four children – aged 12, 14, 15 and 16 – needed to set off by themselves on the gruelling and precarious 5,000-km (3,100-mile) journey from Kashgar, near China’s border with Pakistan, to the eastern coastal city of Shanghai to apply for Italian visas in June 2020.

On the road, they faced many great dangers and challenges. Regulations prohibit children from buying train or flight tickets and from travelling on their own in China. Due to discriminatory policies and local government edicts, hotels often refuse to accommodate Uyghur people, claiming there are no rooms available. Despite the adversity, the children persevered and managed to reach Shanghai.

“Now my children are in the hands of the Chinese government and I am not sure I will be able to meet them again in my lifetime.”

– Mihriban Kader

When the children finally reached the gates of the Italian consulate, valid passports in their hands, they could almost feel as if their parents were on the other side waiting to hug them.

Their excitement quickly turned to despair when they were denied entry into the consulate. They were later told family reunification visas could only be issued in the Italian embassy in Beijing, but at that time people could not travel due to the strict lockdown in Beijing in June 2020. With hearts shattered, the children waited outside the consulate, hoping that somebody would come out and help them. Instead, a Chinese guard came over and threatened to call the police if they did not leave.

Refusing to give in to dejection, the children sought assistance from several travel agencies to apply for Italian visas. On 24 June, all four were seized by the police at their hotel in Shanghai and taken back to an orphanage and boarding school in Kashgar, according to their parents. Had they been permitted to enter the consulate, they might now be reminiscing together with their parents about the daring journey they had just undertaken instead of languishing in the Chinese orphanage system. As it stands, Mihriban and Ablikim fear they might have lost their children forever.

Recommendations

To the Chinese government:

- Ensure that children are allowed to leave China to be reunited as promptly as possible with their parents, if that is preferred by them, as well as with siblings already living abroad.

- End all measures that impermissibly restrict the rights of Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic groups to freely leave and return to China.

- Provide full and unrestricted access to UN human rights experts, independent researchers and journalists to Xinjiang to conduct independent investigations about what is happening in the region.

- Close the political “re-education camps” and release detainees immediately, unconditionally and without prejudice.

- Ensure Chinese diplomatic or consular organs and other public officials and authorities protect the legitimate rights and interests of all Chinese citizens, particularly in providing appropriate assistance with locating their family members in China.

- Ensure that everybody from Xinjiang is able to regularly communicate with family members and others without interference, including with those living in other countries, unless specifically justified in line with international human rights law.

- Cease the practice of forced separation of Uyghur children from their parents or guardians, in line with its obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights, unless competent authorities subject to effective judicial review determine that such separation is necessary as a last resort for the best interests of the child;

- Release, as a matter of urgency, all children held in state-run institutions without consent of the child’s parents or guardians.

To other governments:

- Ensure that all Uyghurs, Kazakhs and others have prompt access to a fair and effective asylum process, legal counsel, a thorough assessment of the possible human rights violations or abuses they might face upon return and the ability to challenge any removal orders;

- Make best efforts to ensure that all Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other members of Chinese ethnic groups resident in their countries, regardless of their immigration status, are provided with consular and other appropriate assistance to establish the whereabouts of and contact with their children, keeping in mind the special circumstances in which members of these ethnic groups find themselves presently;

- Make decisions about family reunification with due regard to applicable human rights obligations, in particular under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, by dealing with applications by a child or his or her parents to enter their country for the purpose of family reunification in a positive, humane and expeditious manner.

Read Amnesty International’s full report ‘Hearts and Lives Broken: The Nightmare of Uyghur Families Separated by Repression’ featuring all six stories: