Dylan Voller, a boy who was tortured at Don Dale detention centre, has been released on bail from prison eight months early, to participate in a youth rehabilitation program.

What happened?

Dylan Voller shot to national attention as one of the young boys abused and tortured by NT juvenile detention centre guards, as exposed by Four Corners. The image of the young man, hooded and strapped to a restraint chair sparked a national outcry from the public.

On Monday 6 February, 19-year-old Dylan was released on bail from prison to take part in a rehabilitation program in Alice Springs. Dylan will complete a sixteen-week placement at the BushMob program, which helps young people get their lives back on track.

In December, the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory heard from Antoinette Carroll, a youth justice advocacy project coordinator at the Central Australian Legal Aid Service (CAALAS), who said there had been “an overwhelming lack of therapeutic support in place” for Dylan ever since his entry into the prison system.

“Sadly, diversion wasn’t really made available to him, and it should have been, given the low level of his offending. Young people need love and someone to talk to, not to be locked in a cell with nothing to do for days on end.”

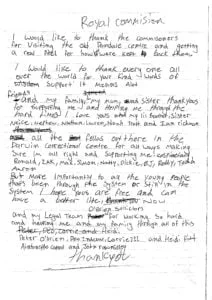

In a letter Dylan read out to the Royal Commission, he states “I would like to thank everyone all over the world for you kind words of support. It means a lot.”

“Young people need love & someone to talk to, not to be locked in a cell with nothing to do for days on end.”

How did Amnesty respond?

Amnesty International Australia has repeatedly raised concerns about tear gassing and other abuses in Northern Territory youth detention centres, and in the past five years has also responded to similar serious allegations in two other states.

We have been calling for youth detention centres to be independently inspected by Australia ratifying the UN Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT). Australia is currently a signatory to OPCAT, but has not yet ratified it. Ratification would mean Australia has to set up a mechanism for independent inspections and reporting on detention centres.

The issue in depth

On 26 July 2016, ABC’s Four Corners Program screened footage from the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre in Darwin, Northern Territory which showed prison officials abusing and torturing detained teenage boys from 2010 to 2015.

In a series of scenes, boys were knocked to the floor and verbally abused, or forcibly stripped and then left naked and alone in locked rooms. Some were kept locked in their cells for almost 24 hours a day with no running water and little natural light. Other footage shows detained Indigenous children being tear gassed.

One particular video shows Dylan being hooded and strapped to a restraint chair after he was deemed at risk of self-harm. The practice of hooding, most notably used at Guantanamo Bay and in the Abu Ghraib prison camp, constitutes a form of torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

After the footage of the abuse aired, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull ordered a Royal Commission into the abuse at the detention centres. Now 19, Dylan has been giving evidence as part of the Royal Commission.

In 2015–2016, Indigenous young people were 24 times more likely to be in detention than non-Indigenous young people. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people make up about six per cent of the Australian population of 10 to 17-year-olds, but more than half (54 per cent) of those in detention.

What’s next?

Amnesty International will continue calling for leadership from the Prime Minister in addressing the over-representation of Indigenous kids in prisons, including funding community-led programs like Bushmob to help kids avoid the justice system and rehabilitate where they have been in detention.

We’ll be closely following the Northern Territory Royal Commission and asking the Federal Government to use its findings to form a national plan through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) to address the overrepresentation of Indigenous kids in Australian prisons.