Over the past decade, governments and the media worldwide have maintained an alarming anti-refugee narrative, nourished by misconceptions and scare tactics. This narrative often portrays refugees as threats to national security, drains on resources, and even as potential terrorists. Such rhetoric not only promotes discrimination and xenophobia but also makes people forget about the struggle of millions fleeing conflict, persecution, and poverty. The impact of this narrative is deep, as it directly affects refugees trying to rebuild their lives in safety. By perpetuating myths and stereotypes, governments and the media create barriers for refugee integration, undermine social tensions, and ultimately interfere with global efforts to provide sanctuary and support to those in need. It is crucial to debunk these myths and challenge this harmful narrative to ensure that refugees can access the safety and opportunities they deserve.

Before we start debunking myths about refugees, are you sure you know the differences between a refugee, an asylum seeker and a migrant? Here’s a very brief explanation, but you can also check our Terminology guide for more information.

A refugee is a person who has fled their country of origin and is unable or unwilling to return because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted because of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

An asylum seeker is an individual who is seeking international protection. In countries with individualised procedures, an asylum seeker is someone whose claim has not yet been finally decided on by the country in which he or she has submitted it. Not every asylum seeker will ultimately be recognised as a refugee, but every refugee is initially an asylum seeker

Whereas a migrant is someone who leaves their home country to pursue opportunities or improved safety in new locations (for example those who are climate displaced). Migration can be voluntary or involuntary, typically influenced by a mix of personal choice and external factors.

Whether intentional or not, false narratives contribute to confusion and encourage division by twisting numbers and facts. In the following list, we address several prevalent myths and misunderstandings about refugees in Australia.

Myth 1: Refugees don’t contribute to their host country

The myth that refugees don’t contribute to their host country is simply untrue. Refugees have been proven to make important contributions to Australian society in areas including volunteering, social engagement, business ownership and workforce participation.

The Centre of Policy Development reported that refugees in Australia are more than twice as likely to establish their own businesses compared to the average Australian. Supporting refugees to launch businesses in Australia could potentially add $1 billion to the Australian economy over 10 years. Highlighting the entrepreneurial feats of refugees not only increases jobs domestically, but also helps contradict the myth that refugees are ‘burdens’ on the Australian economy.

In fact, if Australia had increased its refugee intake by 44,000 by the end of 2023, we would have been able to add an additional $37.7 billion to the Australian economy according to Oxfam. But it’s not too late, and we can still campaign and make a difference for the lives of refugees by increasing our intake.

On top of that, refugees contribute in a special way to Australian society by offering a unique perspective from their own cultures and background. They often translate their experiences into an Australian context to make meaningful contributions. Some notable Australian refugees include: Judy Cassab [Artist], Tan Le [IT entrepreneur], Deng Adut [Criminal Lawyer and 2016 Australian of the year] and many more which could take up multiple pages.

Myth 2: Most refugees are ‘economic migrants’

The myth that refugees are seeking asylum for economic benefit is divisive and destructive. Not only does it frame refugees as seeking an ‘easy way out’, but also denies the legitimacy and seriousness of their claims.

People usually don’t want to leave their family, their friends, their communities and everything that makes them feel at home. Most people applying for asylum do so to escape war, human rights abuses and violence. The term ‘economic migrant’ implies that refugees move freely with the purpose of improving their financial situation for personal gain. The term also has xenophobic connotations, and often suggests in politicians public discourses that ‘economic migrants’ move to ‘steal’ Australian jobs and social benefits.

Analysis of government records by the Refugee Council of Australia shows that an overwhelming 81% of people who arrived to Australia by boat from 1976-2015 were found to be refugees. This number doesn’t include those who withdrew their applications or those with unresolved cases.

Myth 3: Australia shouldn’t have to accept any refugees because foreign conflicts aren’t Australia’s problem

Australia’s presence in International Affairs has been marked by active engagement and deployment of troops to various conflict zones across the globe, particularly in regions like the Middle East and North West Africa. The consequences of our involvement underscore our responsibility to provide assistance and protection to asylum seekers. This responsibility is grounded in moral, legal, humanitarian, and historical considerations, highlighting the importance of upholding principles of compassion, solidarity, and respect for human dignity on the global stage.

Moral Obligation: Australia’s involvement in international affairs through military support can lead to displacement and refugee flight, creating a moral duty to aid those fleeing persecution, violence, and instability, especially if Australia’s actions have contributed to these crises.

International Legal Obligations: Australia’s international legal commitments, including the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, mandate providing asylum and protection to refugees regardless of nationality or displacement circumstances.

Humanitarian Considerations: As a country that values human rights and humanitarian principles, Australia must compassionately respond to asylum seekers’ urgent needs for safety, shelter, and support, given their often-traumatic experiences.

Global Citizenship: Australia’s participation in international affairs positions it as a global citizen with responsibilities beyond its borders. This includes taking proactive steps to address the root causes of displacement, promote peace and stability, and contribute to international efforts to protect and assist refugees.

Historical Context: Australia’s history of accepting refugees since World War II highlights its capacity and willingness to provide refuge to those in need, reinforcing its duty to assist asylum seekers from regions where it has engaged in military operations.

Myth 4: Refugees are responsible for overcrowding in Australia

The blaming of refugees for overcrowding in Australia is a finger-pointing tactic that’s often used by politicians to shift the blame away from proper funding for infrastructure and affordable housing.

According to the UNHCR, Australia currently hosts almost 60,000 refugees and 80,000 asylum seekers, which is a total of 140,000 people. The total population of Australia being about 26.5 million people, refugees and asylum seekers only represents about 0.50% of the population.

These tactics are similar to those used to blame refugees for ‘stealing’ Australian jobs. Governments have known about increasing population numbers for decades, but have failed to make any real policy changes while continuing to cut taxes for mega-corporations.

Myth 5: People with a legitimate claim will be granted asylum

We often assume that asylum seekers with legitimate reasons for fleeing their country (war, persecution, denial of human rights) are always granted a visa and a safe place to stay. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. A prime example of this is the case of Rohingya people in Myanmar, who face constant threats and persecution, many of whom are still being denied asylum in neighbouring countries or have been waiting for years on end for a durable solution.

In October 2023, Craig Foster, Former Socceroo and Amnesty International Australia Ambassador, travelled to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, which is the largest refugee camp in the world. What he reported from his trip sadly illustrates how people in urgent need of asylum are being denied full recognition as refugees.

“We can’t go out for work because as soon as we try, the police catch us and bring us back here. We can’t afford to eat what we want, nor can we afford to buy what we need.” Rahim*, a young Rohingya man in Cox’s Bazar refugee camp

In 2014, the Abbott government introduced Temporary Protection Visas and Safe Haven Enterprise Visas, as well as the highly unfair ‘Fast Track’ process, which discriminated against a specific group who arrived by boat. Not only did the government remove the definition of refugee from the Migration Act, they also denied this group of asylum seekers arriving by boat permanent protection visas (only offering three or five year visas at most), keeping them in perpetual state of limbo, never to be reunited with their family. While the current government has allowed those on TPVs and SHEVs to apply for permanent visas, they still face issues reuniting with their family and thousands who were rejected under the unfair ‘Fast Track’ process now risk being returned to danger.

“I don’t care about myself, I’m losing my mental health. Mostly what hurts me is my family are in a very insecure place, I just recently helped them move out of those places and find a new place. I am facing insecurity with my family. My friend says I would not be able to do anything for the community because I have lost my mental health. I want my family to be better than me. I wish the Australian government would do something for these people, first those who are here, then they can help and do for other people.” – Hazara man from Afghanistan, now in Australia, whose family’s still stuck in Afghanistan

Myth 6: The conditions in Australia detention centres aren’t that bad

Australian detention centres have consistently been criticised for breaching the human rights of detained asylum seekers. They restrict the right to basic freedoms and impose unnecessarily cruel conditions upon asylum seekers. Some off-shore detention facilities in Australia have even been reported to violate the International Convention Against Torture. Detention for asylum seekers in Australia who arrive undocumented is mandatory. As of 31st December 2023, there were 872 people in immigration detention facilities. The average period of detention is almost three years.

An inquiry by the Australian Human Rights Commission found that the conditions of these detention centres were prison-like, with evidence of unnecessary handcuffing of vulnerable groups. Handcuffing has become almost routine, even in situations where it’s completely unnecessary such as waiting rooms for doctors and counsellors.

The report also highlights privacy breaches and the needless use of violence by officers, using the guide of compliance while abusing their power and inflicting serious injury onto detained asylum seekers.

Mostafa (Moz) Azimitabar, as an example, is a Kurdish-Iranian refugee. He was unlawfully detained for 14 months in Melbourne-based hotels with no access to the outside world. He suffered profound psychological harm as a result of near-constant solitary isolation, surveillance, physical ‘pat downs’ and the denial of basic necessities of life such as fresh air and social contact.

Since the recent NZYQ ruling issued by the High Court of Australia on November 28th 2023, indefinite detention for people the government cannot is now unconstitutional and unlawful. However mandatory detention for people who arrive undocumented remains, with individuals remaining in detention, often for years, while they are processed for protection.

Myth 7: Australia’s refugee intake is generous enough already

Australia’s refugee intake, despite ranking high in resettlement numbers, isn’t as generous as it appears. In fact, Australia ranked 3rd overall and 2nd per capita in refugee resettlement between 2013 and 2023, which can seem great at first glance. But while Australia received 13.1% of resettled refugees globally during this period, it only recognised 0.21% of the total 22.98 million people granted refugee status worldwide. So the overall recognition is very low both in absolute numbers and relative to its population and wealth. In simple words, this means a lot more can be done.

In terms of per capita intake, Australia falls significantly behind countries like Lebanon, Jordan, and Montenegro, ranking 72nd with 2.08 refugees per 1000 population. In addition, when considering the relative wealth of the nation, Australia’s refugee intake is even less impressive, ranking 109th with 35 refugees for every $1 billion of GDP. This places Australia far behind countries like Chad, Uganda, and Lebanon, which host significantly more refugees relative to their GDP.

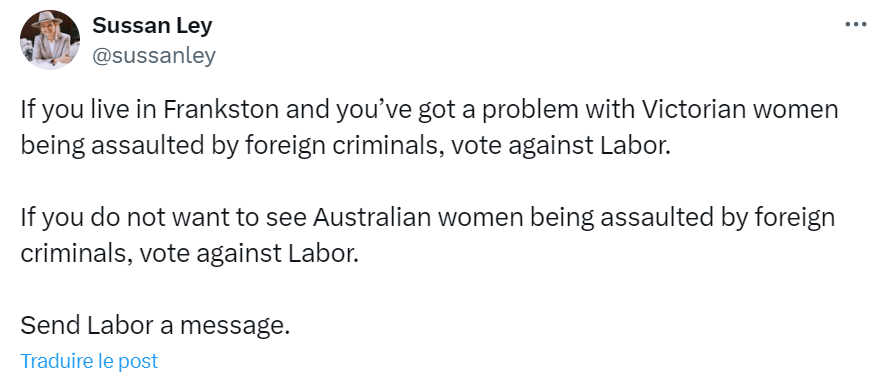

Myth 8: Australia’s tough position on asylum seekers is necessary to keep dangerous criminals out

The myth that asylum seekers and refugees are ‘dangerous criminals’ is used by politicians and the media to create fear and division, primarily for cynical political ends. Asylum seekers and refugees go through extensive background and security checks before they’re granted protection and the right to live in Australia.

Recently this myth was used by the Federal Opposition and Peter Dutton to fuel attacks and criticisms of people released from detention, even though embarrassingly one of the individuals they named publicly was cleared of any suspicion. Their persistent use of accusatory language against a former detainee shows the toxic anti-refugee sentiment that still exists. It needs to change to ensure we can have sensible conversations about how to provide those in need with durable solutions.

Myth 9: Refugees can’t adjust to Australian culture and values.

Refugees, like any other immigrants, come from diverse backgrounds and have unique experiences. Even though adjusting to a new country takes time, refugees are able to successfully integrate into Australian society, all while contributing to their communities, the broader community and embracing Australians’ multicultural values.

Myth 10: We can’t do anything about the global refugee crisis.

Contrary to popular belief, Australia has the ability to greatly impact the global refugee crisis by changing its policies and increasing its intake of refugees. Australia is one of the least densely populated places in the world and has ample resources and money to provide a safe place for refugees to live.

The government must also respect international law and end policies, such as sending asylum seekers to offshore detention centres, in breach of our international obligations.

On an individual level, you can attend events, sign petitions and contact local members of parliament to share your concerns about Australia’s asylum seeker policy and the treatment those seeking protection receive.

Amnesty works to raise Australia’s refugee intake and campaigns to make sure governments honour their shared responsibility to protect the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum. We condemn any policies and practices that denies the rights of people on the move.

With our campaigns, we put pressure on governments to honour their responsibility to protect every single person’s rights. They must make sure that refugees, people seeking asylum and migrants are safe, and aren’t arbitrarily detained, tortured, discriminated against or left living in poverty.