In less than 40 years, 124 countries have abolished the death penalty – and here’s why the rest should end it too.

Chan and Sukumaran

Marched in handcuffs across the tarmac by a group of heavily armed officers wearing balaclavas and thick helmets, the bare faces of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran appeared even more tragic.

The blurry images showing them being taken onto the plane headed for Nusakambangan Island Prison highlighted the inhumanity of the fate that Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo is adamant they will face.

After more than 10 years in prison, they are among the next group whom Widodo says will be executed.

Chan, 31, and Sukumaran, 33, were convicted in Indonesia in 2006 for drug trafficking. Their highly-publicised plight represents all that is wrong with the death penalty.

Death penalty in Indonesia

Amnesty International has been campaigning to end the death penalty since 1977. When this campaign began, only 16 countries had ended capital punishment; now 140 countries have abolished the practice.

Despite Widodo’s claims that he’s carrying out executions to serve as a warning about drugs, there is in fact no evidence that the death penalty serves as a deterrent. Nor is it humane.

After a four-year moratorium on the death penalty, Indonesia resumed executions in March 2013.

In Indonesia, death sentences are carried out by firing squad with the prisoner in front of 12 gunmen, three of whose rifles are loaded with live ammunition, while the other nine are loaded with blanks. The squad fires from a distance of between five and 10 metres.

The prisoner has the choice of standing or sitting, and can decide whether to have their eyes covered by a blindfold or hood.

A single shot is fired from each rifle, aimed at the chest. If that does not kill the prisoner, the commander will fire a point-blank shot to the head. No witnesses or family are allowed to be present. According to a Catholic priest who witnessed the executions of two Nigerians in Indonesia in 2008, it took them up to eight minutes to die and they “were moaning in pain”.

Long, slow deaths

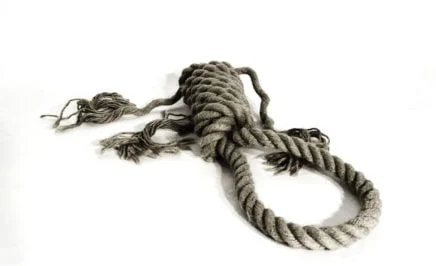

A drawn-out death is reflected in many of the stories about executions internationally. In Iran, it took 12 minutes of Alireza M hanging by his neck before he was pronounced dead.

The 37-year-old was hanged in Bojnourd prison in north-east Iran in October 2013 after being convicted of drug offences.

Alireza was found to be alive and breathing in the morgue when his family came to collect the body. The execution had failed. Alireza went on to have his sentence commuted by the Iranian justice system, and was handed a life sentence instead.

After 18-months of no executions, Vietnam resumed using the death penalty in August 2013.

Nguyen Anh Tuan, convicted for murder in 2010, was reportedly executed in the Ha Noi Police prison through lethal injection – the first execution in the country since around January 2012.

“In the last 40 years, more than 140 death row inmates have had their innocence proven. This margin of error alone should be enough to point out the flaws in the system if the method of execution hasn’t.”

Diana Sayed is a human rights lawyer and crisis campaigner for Amnesty International

The European Union export ban on the chemicals needed for lethal injections has meant that Vietnam faces a shortage of drugs needed to carry out executions.

Five Yemeni men in Saudi Arabia were beheaded and crucified publicly in May 2013, with pictures emerging on social media appearing to show five decapitated bodies hanging with their heads wrapped in bags.

Texas, the most-prolific death penalty state in the US, executed its 500th person in June 2013 – a worrying landmark in America’s capital punishment history since state-sanctioned killing resumed in 1977.

Kimberly McCarthy was administered a single, lethal dose of pentobarbital, a barbiturate. She was pronounced dead 20 minutes later.

To date, the US remains one of the top five countries carrying out executions globally.

Even more alarming is that death sentences can be wrong. Just last week the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals issued a stay of execution in the case of Rodney Reed after new scientific evidence came to light that established his probable innocence. He was due to be put to death on March 5.

In the last 40 years, more than 140 death row inmates have had their innocence proven. This margin of error alone should be enough to point out the flaws in the system if the method of execution hasn’t.

This article was first published on Business Insider Australia.

Learn more about Amnesty International Australia’s campaigns to end the death penalty and how you can help save lives today.