Australia has a rich history of championing human rights through protest. Today, weekly demonstrations expressing solidarity with the Palestinian community highlight the impact of collective action. These protests have galvanised the public and transformed the conversation.

Since colonisation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders have been at the forefront of ongoing protests for Indigenous Rights. On 26 January, First Nations people and our allies will march for Indigenous justice Australia-wide to mark Invasion Day/Survival Day. (Some still refer to this day as ‘Australia Day’).

Why We Need to Protest

Protestors are often demonised in the press, stereotyped as bleeding-heart lefties causing a nuisance. We’ve all seen news reports where drivers on their morning commute fume over the inconvenience. They might say something like “I support them in principle, but why do they have to get in the way?”

It’s easy to forget that the rights we enjoy today weren’t just handed to us out of the blue. We had to fight for them, to stand up and be noticed. And that means getting in the way. Take any human rights win in Australian history, and you’ll probably find a line of cars backed up behind it, furiously honking their horns.

This is doubly true of Indigenous rights. We remember the big breakthroughs, like establishing native title or Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations. First Nations people have had to fight harder for smaller wins. Activists often don’t get to see the change they were fighting for within their lifetime. We’re only able to do this work now because of the Elders who paved the way before us.

Let’s take a look at how three historic protests advanced Indigenous rights in Australia.

1967 Referendum

May, 1967: Australia held a referendum asking the Australian people to vote on recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Constitution.

The referendum came after 10 years of campaigning and the formation in 1958 of the first national Indigenous pressure group, the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA).

Across the 1950s and ‘60s, activists organised petitions to gain public support for constitutional change. FCAATSI campaigned for the ‘yes’ vote with support from unions, churches and the Labor party.

This was the most successful referendum campaign in Australian history. Almost 91% of Australians voted ‘yes.’ This meant that Aboriginal people would be counted as part of the population, and the Commonwealth could make laws on their behalf.

Aboriginal Tent Embassy

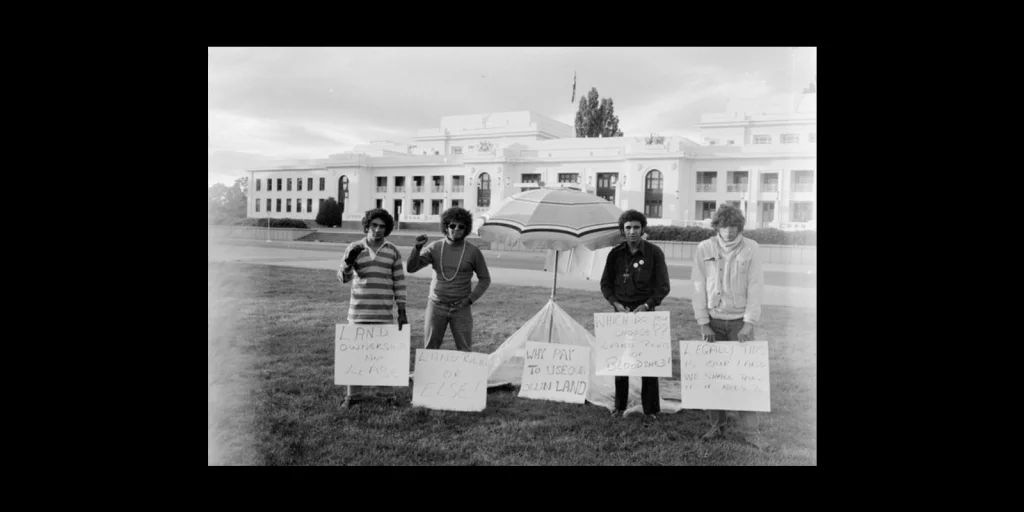

In 1972, the McMahon government announced a new system that impacted on Indigenous land rights. The system forced Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities into 50-year leases rather than granting independent ownership of traditional land. Many Indigenous groups were spurred to action to protest this injustice.

On 26 January 1972, four First Nations men – Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bertie Williams and Tony Coorey – set up a beach umbrella on the lawns opposite Parliament House in Canberra.

The Embassy won support from around the country. It attracted both First Nations and non-Indigenous activists to join in solidarity over the land rights movement. Groups from the Embassy went on protest marches, lobbied the Government and spoke at community forums. Through protest, they brought awareness of land rights issues to the Australian public.

Over the years, the Embassy was torn down by police and had to be rebuilt. It’s had a number of different layouts in locations across Ngunnawal Country (Canberra), including the site of the current Australian Parliament House. The issues being protested have fluctuated over the years as well, depending on events in the political landscape. The Embassy now focuses on Indigenous rights issues including sovereignty and the right to self-determination.

John Newfong wrote in ‘Identity’ in 1972: “With its flags fluttering proudly in the breeze, the Aboriginal Embassy on the lawns opposite federal parliament has been one of the most successful press and parliamentary lobbies in Australian political history.”

With its flags fluttering proudly in the breeze, the Aboriginal Embassy on the lawns opposite federal parliament has been one of the most successful press and parliamentary lobbies in Australian political history.

John Newfong, ‘Identity’ 1972

1988 Bicentenary Protest

On the 26th January, 1988, Australia was set to celebrate the 200 year anniversary of the first fleet arriving on Bidjigal and Gadigal Country (Botany Bay and Sydney Cove). The planned events included a re-enactment of the first fleet’s arrival, a parade and concerts.

At the same time, more than 40,000 First Nations and non-Indigenous allies staged the largest march ever seen at that time in Sydney. They marched against the celebration of colonisation and dispossession, with buses travelling from rural and remote communities as well as interstate.

The protest marched through Sydney, ending at Hyde Park. Protestors shone a spotlight on poor social, health and education outcomes, as well as high imprisonment rates and deaths in custody for First Nations people. It was also a statement that, while the rest of Australia celebrated the arrival of the first fleet and all that came with it, First Nations people have survived, and are still here: “White Australia has a Black history”.

During the speeches at Hyde Park, activist Uncle Gary Foley said: “Let’s hope Bob Hawke and his Government gets this message loud and clear from all these people here today. It’s so magnificent to see black and white Australians together in harmony. This is what Australia could and should be like.”

Let’s hope Bob Hawke and his Government gets this message loud and clear from all these people here today. It’s so magnificent to see black and white Australians together in harmony. This is what Australia could and should be like.

Uncle Gary Foley

Stay safe, stay informed and make your voice heard!

On 26 January, we’ll be at demonstrations for Invasion/Survival Day around the country. We march to recognise the heartache and pain caused by colonisation, to demand rights and justice for Indigenous people, and to commemorate those who fought this fight before us. We want you to come on this journey with us, and we hope to see you there.

Kacey Teerman and Rach McPhail