Fiona* is devastated at how much Queensland’s justice system failed her son.

In January, Fiona’s 15-year-old son Mark* spent three weeks in the Brisbane City Watch House for stealing chocolates and paint cans from a shop.

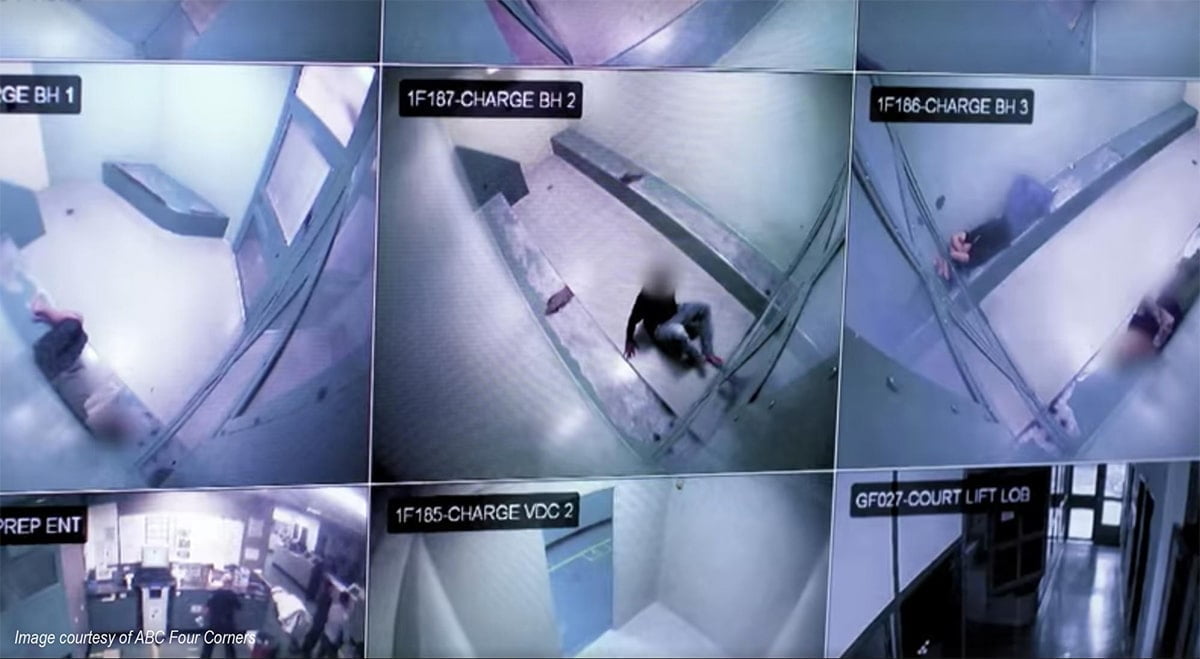

Police took Mark to the Brisbane City Watch House, a maximum security detention facility designed to temporarily hold adults. From there, Mark should have been transferred to the Brisbane Youth Detention Centre. But the youth prison was full so Mark’s stay at the police watch house continued.

In a watch house, children like Mark are treated as adults: kept alongside them; subjected to strip searches and solitary confinement; and deprived of the education their peers receive in school or youth prisons.

Mark spent his time alone in a small cell. Hours turned to days, then weeks.

Navigating a broken system

Fiona is an Indigenous woman living in South Brisbane. She’s an active member of her community, and she worked at her local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health service for many years.

From chatting with Fiona, it’s clear that she loves Mark an enormous amount. Mark is a talented and passionate dancer and artist. He’s also diagnosed with autism and Asperger’s syndrome, two developmental disorders. Mark does not always communicate freely with Fiona, and he struggles with anger management.

Fiona’s attempts to navigate Queensland’s broken justice system left her incredibly frustrated. First, Fiona was kept in the dark while Mark was detained. For two weeks, no one called her. She didn’t know where Mark was being held – but she guessed Brisbane’s youth detention centre.

Fiona’s guess should have been correct – children in detention should be kept in youth prisons, facilities which cater to childrens’ needs. Queensland’s police manual states that police watch houses are only to be used as a last resort for detaining children, and that children must not be kept in watch houses for overnight stays.

Amnesty International recently found 2,655 breaches of international standards, Queensland regulations and the Queensland Police Operational Procedures Manual in the Brisbane City Watch House in 2018.

Then, Fiona’s bail request was denied: two weeks had not been enough to complete a psychometric assessment for Mark.

This is common in Queensland’s broken bail process – poor funding means bail assessments are incredibly slow. Since September 2018, the number of children held in Queensland on remand (that is before their guilt or sentence have been determined) has not fallen below 80 per cent. Some of these children are innocent.

Fiona worries that the unwelcoming environment and constant police presence would have likely aggravated Mark’s developmental disorders.

Calls for support unheeded

Fiona’s frustrations with the system are not new — she says Mark has been left to suffer from a very young age. Fiona has been through years of pain while begging for support.

“He has practically missed 90 per cent of his education since Year Two, facing almost weekly suspensions,” she says.

“I’ve been crying out for help for years, we have tried to get psychologist support but when it has come to a follow up, we’ve had nothing. He has been traumatised and brutalised by the system.”

Programs do exist to help families, such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service in Brisbane who provide community medical care and youth services for in-need families. However, many families continue to feel unsupported. Fiona spoke anecdotally of holiday programs with informal behavioural criteria — Mark had been rejected multiple times from such programs.

Community-led initiatives lacking

Another problem is that the diversion programs that do exist are not community-led. The staff “don’t know the local cultural sites, stories, history, dream time stories, or community Elders,” Fiona says.

Fiona longs for a program that engages local Indigenous children with their culture and Elders, and taking them to live on country. However, she says her community has never enjoyed one.

“These kids are growing up without an identity, they need to understand their cultural identity. They need people to take an interest in them and do positive things with them”.

Mark is now living in Rockhampton with his father. Rockhampton has helped Mark. He has learnt more about his culture and made positive relationships within his father’s community.

“It’s sad to say, but I’m relieved to have him away from me [to his father in Rockhampton], otherwise, I don’t know what would be happening to him now.”

Looking to the future

Across Queensland, there are countless others like Mark and Fiona – families deprived of greatly-needed support, who then fall victim to a brutal prison system. As of 10 May 2019, Brisbane City Watch House held 89 children — at least half of them were Indigenous and at least three were 10 years of age.

Fiona is passionate about improving her community. She and a group of Indigenous women hold poetry nights and sell artwork (including artwork made by Mark) to provide local families with food and household appliances.

Fiona tells me her story is the community’s story. We must demand governments stop the cyclical disenfranchisement of Indigenous communities everywhere.

By Liam Thorne

* Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.