- New centres offer less protection than previous camp

- New centres do not meet refugees’ basic needs

- Refugees live with constant fear of violence

- Australia must end policy of cruelty and neglect

The Australian government’s abandonment of hundreds of refugees and asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea is a form of prolonged punishment, Amnesty International said in a new report.

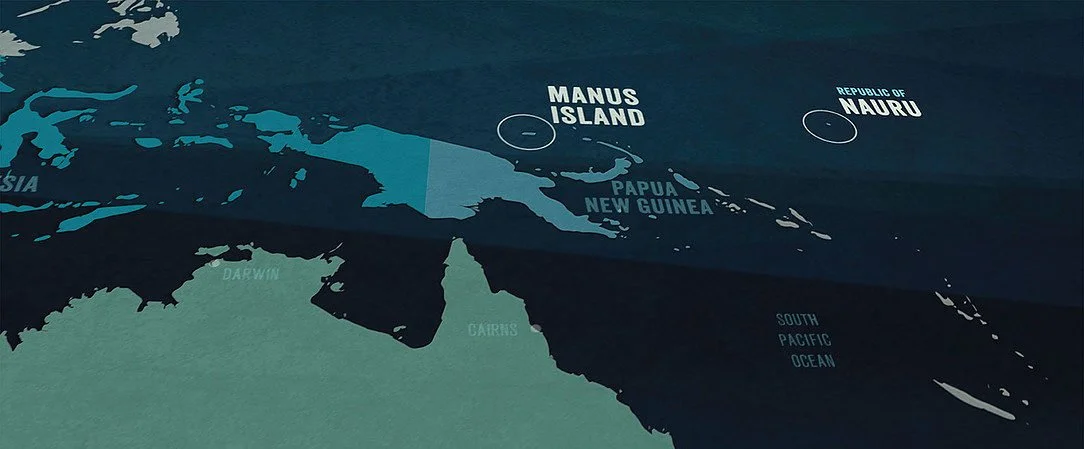

Punishment not protection: Australia’s treatment of refugees and asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea documents how, since refugees were forcibly evicted from the Manus Island detention centre in November 2017, the Lorengau centres they were moved to have proven inadequate and even less safe, with violence from the local community a constant threat.

The psychological trauma of prolonged detention has taken a serious toll on refugees, with 88% suffering from depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. Despite this, the new centres are only served by one small medical clinic and a public hospital, which are far from adequate to meet the refugees’ needs.

“Moving refugees and asylum seekers from one hellish situation to another is not a solution, it is just prolonging these desperate men’s suffering. The new centres on Manus Island are not just a safety risk but also leave those who live there without basic services,” said Kate Schuetze, Amnesty International’s Pacific Researcher.

An unsafe situation

Amnesty International’s research – based on on-the-ground interviews with 55 refugees and asylum seekers – reveals that the new facilities are far from safe and fail to address the fundamental problems with Australia’s offshore processing.

Several refugees have been violently attacked by locals in recent years on Manus Island, in cases that have not resulted in any prosecutions. The newer facilities offer even less protection than the previous centre – they are not only closer to Lorengau town, but also lack basic security infrastructure such as fences.

Many refugees told Amnesty International that they were too afraid to leave the centres due to the risk of violent attacks or robberies by locals. The police’s repeated failures to investigate attacks or hold those responsible to account has created a climate where attackers can expect they will not be caught or punished, which has further undermined refugees’ trust in the authorities.

Joinul Islam, a 42-year-old Bangladeshi man, said: “I’m not coming to Lorengau because Lorengau is a very dangerous place. Three months ago, I came to Lorengau and someone cut my [arm]. They took my mobile and my money. It’s a very dangerous place… I don’t like to come to Lorengau.”

The refugees have been caught in a hostile situation, where there have been repeated roadblocks by the landowner, disputes between service providers and protests by local residents.

In recent weeks, a stand-off between rival security companies has added to the sense of instability. Guards from a Manus company have reportedly driven guards from a company contracted by the Australian government out of some of the facilities. This has resulted in confusion about who is in charge of providing security to refugees.

“Refugees told us they had been robbed and assaulted in both Manus Island and Port Moresby. The police have refused to act even on the most serious cases of violence. The bottom line is that Papua New Guinea does not provide a safe or sustainable solution for the refugees sent there by Australia,” said Kate Schuetze.

On 21 January 2018, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) also noted “while no formal curfew is in place, local police have advised all refugees and asylum-seekers to return to their accommodation by 6pm each evening to mitigate security risks”.

Restrictions on freedom of movement and ability to work

Refugees remain subject to severe restrictions on their freedom of movement. Most are unable to leave designated accommodation facilities on Manus Island or in Port Moresby. They are reduced to surviving on a basic living allowance that is insufficient to cover their food, medicine and other expenses.

PNG authorities have failed to provide refugees with regular status, access to travel and identity documents or the ability to obtain work long-term that is essential for the meaningful integration of refugees. Settlement in Papua New Guinea has proven near impossible for those refugees who have attempted it, given the difficulties of earning a living and the constant threat of violence.

Australia must provide a real solution

After nearly five years, the Australian government has provided no viable or sustainable options for the refugees it forcibly transferred to Papua New Guinea. The refugees are effectively forced to choose between returning to grave risk of human rights abuses in their own country or moving to a similarly abusive environment on Nauru.

A lucky few – around 83 so far – have received the “lottery ticket” of being settled in the United States, but this is a lengthy and arbitrary process that is not open to everyone.

“In the short term, authorities in Papua New Guinea and Australia must do everything they can to ensure protection for the refugees. They must ensure their basic needs are met and their safety is not at risk,” said Kate Schuetze.

“Instead of implementing new and creative ways to shirk its responsibility and violate international law, the Australian government must end this wilful policy of cruelty and neglect. It must do the only safe and legal thing, which is to bring these men to its own shores – or, failing that, to a safe third country – and offer them the protection they need and deserve.”

Background

Australia withdrew all services to the initial refugee detention centre on Manus Island – where it has sent hundreds of men since 2013 as part of its illegal “offshore processing” policies – from 31 October 2017. After the men in the centre staged peaceful protests and refused to leave, PNG police forcibly evicted and transferred them to three newer facilities in November.